Normalization of Deviation: Understanding and Mitigating Risks

In the realm of engineering, maintaining stringent standards is crucial for ensuring the safety, reliability, and effectiveness of systems and processes. However, a subtle yet significant phenomenon known as the “normalization of deviation” can undermine these standards, leading to catastrophic outcomes. This article explores the concept of normalization of deviation, its implications, and strategies to mitigate its risks.

What is Normalization of Deviation?

Normalization of deviation occurs when deviations from established standards gradually become accepted as normal within an organization. Over time, these deviations, initially considered anomalies, are no longer perceived as risks but as acceptable variations. This shift in perception can lead to a systematic degradation of quality and safety standards.

The term gained prominence following the investigation of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986. Sociologist Diane Vaughan, in her book “The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA,” highlighted how NASA engineers and managers came to accept technical anomalies as routine, ultimately contributing to the disaster.

How Normalization of Deviation Occurs

Normalization of deviation typically follows a pattern:

- Initial Deviation: A deviation from the standard occurs, but the immediate consequences are not severe. The deviation is documented and noted as an anomaly.

- Repetition and Acceptance: The deviation recurs without significant negative outcomes, leading to a gradual acceptance of the deviation as normal practice.

- Cultural Shift: Over time, the deviation is institutionalized within the organization’s culture. New employees are trained under the revised norms, perpetuating the acceptance.

- Systemic Risk: As deviations accumulate, the overall risk to the system increases, often unnoticed until a significant failure occurs.

Implications in Islam

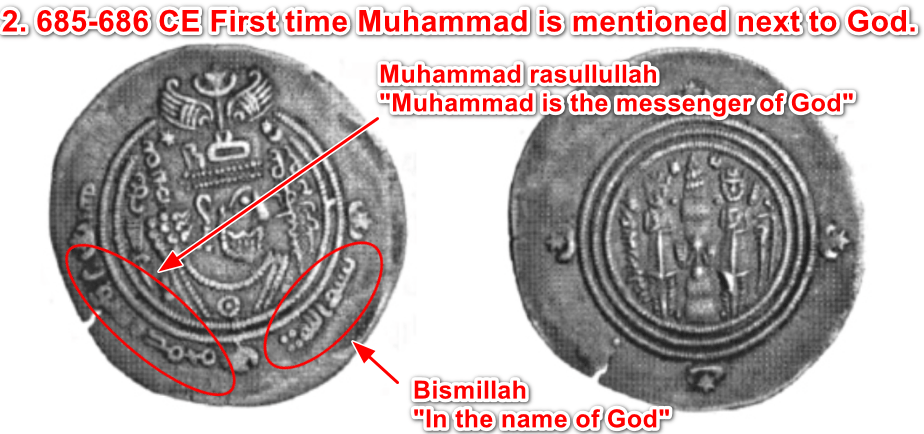

The normalization of deviation poses serious risks in Islam, before 685-686 CE not a single written record exists of Muhammad in the “shahaadah” or testimony of the Muslims. Below is an excerpt of from Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam (*Donner, F.M., 1945)

- Initial deviation: The “double shahada” as it was known occured here to dillineate the Umayyads from their rival the Zubayrs.

- Onset of disaster: This period by the Umayyads mark the onset of Muhammad’s name appearing with increasing frequency next to God Almighty.

- Reputation Damage: This hadn’t happened for 60 years since the prophet’s death, it marked the takeover of pride over God’s authority.

The History

Before the Umayyad Caliphate (responsible for the sharika “association” of Muhammad above), there were two primary caliphates:

- Rashidun Caliphate (632-661 CE):

- Abu Bakr al-Siddiq (632-634 CE): The first caliph, he focused on consolidating the Arabian Peninsula and addressing the Ridda (apostasy) wars.

- Umar ibn al-Khattab (634-644 CE): The second caliph, under whom the Islamic empire expanded significantly into the Byzantine and Sassanian territories. He established many administrative and legal frameworks.

- Uthman ibn Affan (644-656 CE): The third caliph, known for compiling the Quran into a single text. His rule faced criticism and unrest, leading to his assassination. Some believed this is due to the injection of the two false verses in the Quran.

- Ali ibn Abi Talib (656-661 CE): The fourth caliph, whose rule was marked by internal strife and conflict, sparked by Uthman’s assassination, including the First Fitna (Islamic civil war), and eventually his assassination.

- Umayyad Caliphate (661-750 CE):

- Established by Muawiya I after the end of the First Fitna, it was characterized by the establishment of a dynastic rule and the expansion of the empire into Spain (al-Andalus) and parts of India.

The Umayyad Caliphate succeeded the Rashidun Caliphate after a period of conflict and instability, marking a shift from the initially more consultative and tribal leadership of the Rashidun to a more centralized and hereditary rule.

The Tails of the Coins

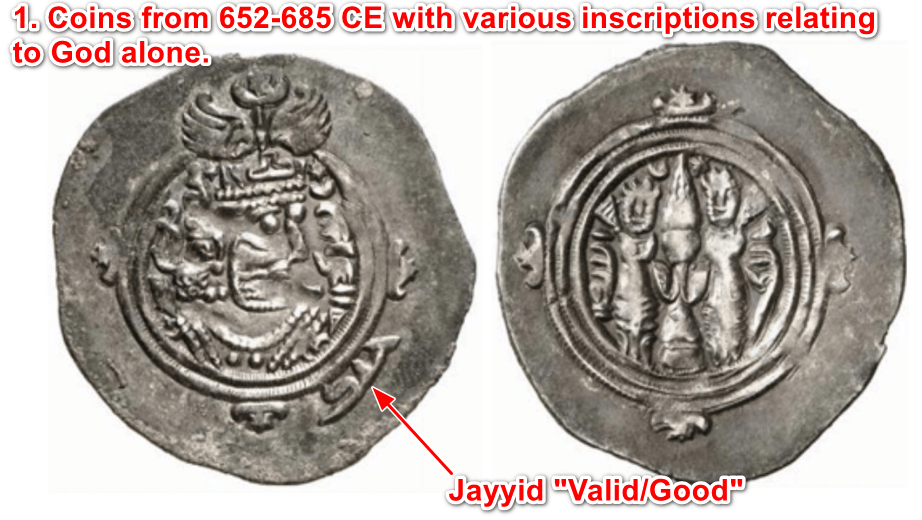

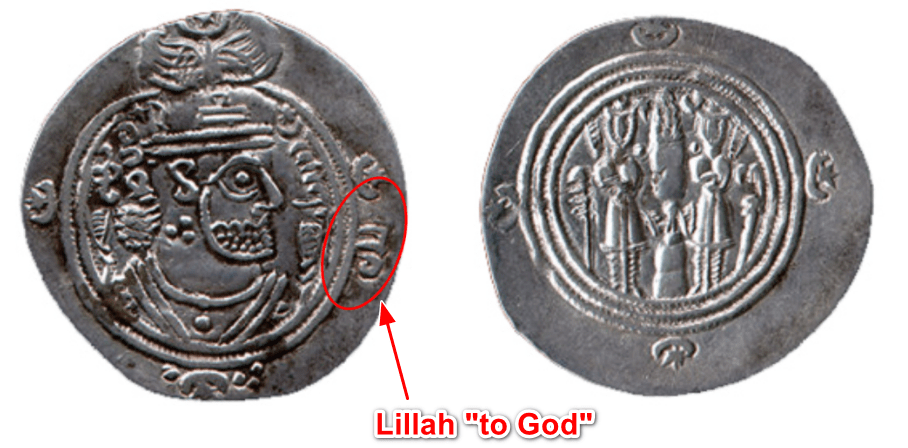

This article by Quran Talk Blog highlights this progression of normalisation of deviations. This article traces the evolution of the Islamic testimony of faith (Shahada) from its original Quranic form, “I bear witness there is no god beside God,” to the dual declaration (Shahadatan) that includes “Muhammad is the messenger of God.” Through an examination of early Islamic coinage, inscriptions, and historical records, the author demonstrates that the inclusion of Muhammad’s name in the testimony was a gradual development, primarily occurring during the reign of Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik (685-705 CE). The first state-sanctioned use of Muhammad’s name on coins appeared around 685-686 CE, with the full Shahadatan not documented until 697-698 CE. The article suggests that this change, occurring about 65 years after the Prophet’s death, was more a product of political and religious consolidation efforts by the Umayyad Caliphate than a practice established by the Prophet himself. The image below showcases this progression in time.

Why did they do it?

The inclusion of Muhammad’s name in coin inscriptions during the Umayyad period, specifically starting around 685 CE, is a significant event in Islamic numismatic history. This change in coinage reflected important political and religious developments in the early Islamic empire.

- Political and religious consolidation:

The Umayyad Caliphate, established in 661 CE, was working to consolidate its power and legitimacy. By including Muhammad’s name on coins, they were asserting their connection to the Prophet and their right to rule as his successors. - Standardization of currency:

Prior to this period, the Islamic empire had largely continued using Byzantine and Sassanid coin designs, with some modifications. The introduction of Muhammad’s name was part of a broader move towards creating a distinctly Islamic coinage system. - Abd al-Malik’s reforms:

The caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685-705 CE) is often credited with initiating major reforms in Islamic coinage. These reforms included the introduction of purely epigraphic designs and Islamic religious inscriptions. - Assertion of Islamic identity:

By placing Muhammad’s name on coins, the Umayyads were making a clear statement about the Islamic character of their empire, distinguishing it from the Byzantine and Sassanid predecessors. - Response to external challenges:

Some scholars suggest that this change was partly a response to Byzantine Emperor Justinian II’s coinage, which featured an image of Christ. The Islamic coins with Muhammad’s name served as a counter-statement.

The introduction of Muhammad’s name on coins in 685 CE was a pivotal moment in Islamic history, reflecting the complex interplay of politics, religion, and cultural identity in the early Islamic empire. It marked a significant step towards “deviating” from other belief systems at the time, alongside marked authority due to perceived connection to Muhammad.

Mitigating the Risks

As listed above, it’s clear that this devolution of faith happened over time and to quote Diane Vaughan was due to “bounded rationality”. It is unclear if the calliphate at the time intended to associate a partner to God but it is clear that their initial motives were to strengthen their foothold of their rule and belief system. What seems harmless at the time has become an institutionalised mantra for Muslims. The only way that you could be accepted as Muslim is to ensure some form of association happens next to God. There’s three general forms of shahadah.

Sunni Shahadah:

“Lā ʾilāha ʾillā-llāh, Muḥammadun rasūlu-llāh”

Meaning: “There is no god but God, Muhammad is the messenger of God”

This is the most common form used by the majority of Muslims worldwide.

Shi’a Shahadah:

The Shi’a often add a third part to the Shahadah:

“Lā ʾilāha ʾillā-llāh, Muḥammadun rasūlu-llāh, ʿAlīyun walīyu-llāh”

Meaning: “There is no god but God, Muhammad is the messenger of God, Ali is the friend/patron of God”

This version emphasizes the special status of Ali ibn Abi Talib in Shi’a Islam.

Simplified/Original Shahadah:

“Lā ʾilāha ʾillā-llāh”

Meaning: “There is no god but God”

This is the simplest form, focusing solely on the oneness of God (Tawhid). Some argue this is the original form as mentioned in the Quran.

It’s worth noting that some smaller Islamic sects or Sufi orders might have additional variations, but these three are the most widely recognized. The first (Sunni) and second (Shi’a) versions are the most commonly used in their respective communities, while the third is generally accepted by all Muslims but is not typically used as the full declaration of faith in most contexts.

So which testimony is correct. How do you diffferentiate right from wrong when the proliferation of religion and the entities you rely on for pillars of truth are wholly incongruent with the Quran. We learn that according to the Quran, the shahadah is:

3:18 God bears witness that there is no God except He, and so do the angels and those who possess knowledge. Truthfully and equitably, He is the absolute God; there is no God but He, the Almighty, Most Wise.

This assertion that we need to inject Muhammad into the testimony as a means of differentiating Muslims from non-muslim is nonsensical. A monotheist according to God will get their due recompense.

2:62 Surely, those who believe, those who are Jewish, the Christians, and the converts; anyone who (1) believes in God, and (2) believes in the Last Day, and (3) leads a righteous life, will receive their recompense from their Lord. They have nothing to fear, nor will they grieve.

To mitigate the risks associated with the normalization of deviation, we can implement several strategies:

- Strict Adherence to Standards: Maintain a culture that emphasizes the importance of adhering to established standards. Regularly review and update these standards to reflect best practices and technological advancements. The best known standard is the Quran. All other forms of literature become deviant over time. God promised to protect the Quran, but not the “hadiths”.

2:2 This scripture is infallible; a beacon for the righteous;

- Continuous Monitoring: Implement robust monitoring systems to detect deviations early. With code 19 and frequent Quranic studies we could detect anomalies and bring the source material back to light, highlight potential deviants, and wipe them out.

15:9 Absolutely, we have revealed the reminder, and, absolutely, we will preserve it.*

Footnote: 15:1 &15:9 The divine source and the perfect preservation of the Quran are proven by the Quran’s mathematical code (App. 1). God’s Messenger of the Covenant was destined to unveil this great miracle. The word “Dhikr” denotes the Quran’s code in several verses (15:6, 21:2, 26:5, 38:1, 38:8, 74:31). The value of “Rashad Khalifa” (1230)+15+9=1254, 19×66.

- Foster a Unified Culture: Encourage open communication and reporting of deviations without fear of retribution. Promote a culture where communication of the truth are prioritized over expediency.

2:174 Those who conceal God’s revelations in the scripture, in exchange for a cheap material gain, eat but fire into their bellies. God will not speak to them on the Day of Resurrection, nor will He purify them. They have incurred a painful retribution.

Conclusion

The normalization of deviation is a subtle but dangerous phenomenon that can undermine religious standards and lead to significant risks. By understanding its dynamics and implementing proactive measures, everyone can safeguard their belief systems, ensuring it follows strict monotheism. As Submitters, it is our responsibility to uphold the highest standards and remain vigilant against the creeping acceptance of deviations.

This is a prevalent and pervasive nature of humanity. We are inherently keen to adhere to societal standards and norms, however, warped and unpalatable they may be. Let us revert to the single source of truth and keep a strict code of adhering to the word of God. Let us remind each other frequently, when we stray of the Straight Path. The true shahadah as it was before deviants is only one:

37:35 When they were told, “Lã Elãha Ella Allãh [There is no other God beside God],” they turned arrogant.

39:45 When God ALONE is mentioned, the hearts of those who do not believe in the Hereafter shrink with aversion. But when others are mentioned beside Him, they become satisfied.*

References:

- “Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam” by Fred M. Donner

- “Islamic History Through Coins: An Analysis and Catalogue of Tenth-Century Ikhshidid Coinage” by Jere L. Bacharach

- “Arab-Byzantine Coins: An Introduction, with a Catalogue of the Dumbarton Oaks Collection” by Clive Foss

- “Coinage and History in the Seventh Century Near East” by Clive Foss

Leave a comment