One of the most striking challenges to Darwinian evolution was articulated by Charles Darwin himself—he recognized that the abrupt appearance of complex life forms in the Cambrian period did not neatly align with his proposed model of gradual, incremental changes driven by natural selection. In his own words, the Cambrian Explosion posed a “major difficulty” because the fossil record seemed to show fully formed phyla with no clear, incremental lineage.

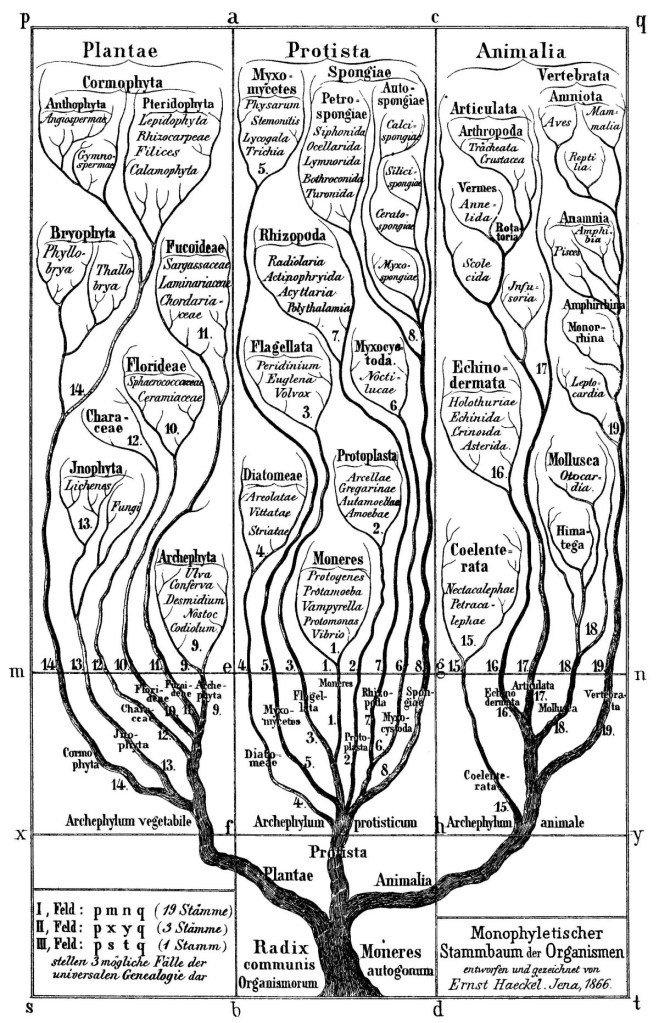

Many years later, Stephen C. Meyer’s seminal work Darwin’s Doubt delves deeper into this conundrum. Meyer underscores that the Pre-Cambrian fossil record, consisting mainly of soft-bodied organisms and the enigmatic Ediacaran fauna, does not credibly anticipate the sudden influx of new animal body plans—new phyla—that appear in the Cambrian. According to standard Darwinian theory, we should see a slow, progressive ramp-up of morphological complexity over vast timescales. Instead, paleontologists find a rapid “branching” of radically different forms in a relatively short geological window. The question thus arises: What power or process could drive such a sudden, information-rich burst of life?

Why the Speed and Suddenness Matter

Darwin’s original model relied on gradualism—tiny mutations slowly accumulating to form new traits. However, for multiple new phyla to appear so suddenly in the fossil record, the sheer quantity of biological “instructions” needed is immense. Neo-Darwinian mechanisms struggle to explain how genetic information and new developmental pathways could arise and become fixed in populations so quickly. If we limit ourselves solely to random mutation and natural selection, the Cambrian record looks, in the words of Meyer, “like a challenge to the adequacy of Darwinian evolution.”

Morphic Resonance and Collective Memory

Looking beyond strictly gene-centric or incremental evolutionary ideas, we encounter Rupert Sheldrake’s concept of morphic resonance. Sheldrake posits that there exists a kind of collective memory or field that organisms tap into, which helps shape their morphological development and behaviors. In this view, DNA alone is not the entire blueprint for how a giraffe becomes a giraffe. Rather, there is a guiding “morphic field” that preserves and transmits the pattern of what being a giraffe entails.

This provocative hypothesis addresses the same conceptual gap we see in the Cambrian Explosion: a sudden infusion of organized complexity that cannot be captured by typical mutation-selection models. Much like the swift arrival of multiple new phyla, Sheldrake’s idea suggests that forms or “templates” exist at a subtle, collective level. That might explain why the mere presence of DNA is insufficient to clarify how an organism “knows” how to actualize itself. If “morphic resonance” holds any merit, it implies a deeper, perhaps intelligently orchestrated, infrastructure to life.

Chomsky’s Universal Grammar and the Language Puzzle

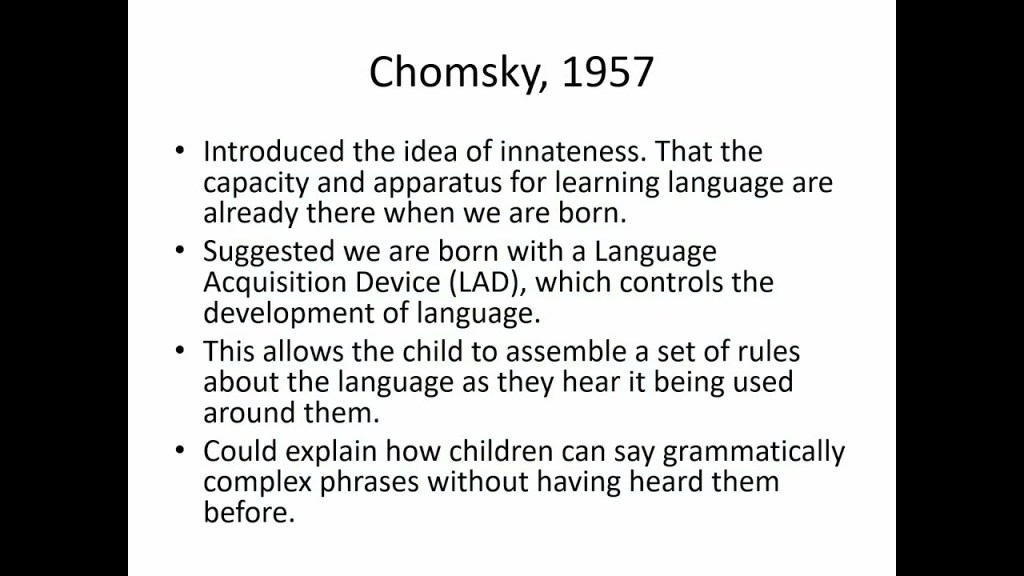

Parallel to the biological realm, there is an equally profound conundrum in the field of linguistics. Noam Chomsky’s theory of universal grammar posits that humans are born with an innate linguistic capacity—a set of cognitive structures that allow any child to acquire whatever language they are exposed to. While this elegantly explains why children so quickly learn complex grammar, it leaves open the evolutionary question: How did such an intricate capacity for language arise in the first place?

Languages themselves morph and evolve over time, yet our brains remain consistently primed to learn them. If we apply a purely Darwinian lens, we might search for intermediate “proto-languages” evolving slowly in tandem with the hominid brain. But the fossil or anthropological record offers sparse clarity on how that might work—especially for the sophisticated grammar rules that appear universal across vastly different tongues. In short, universal grammar successfully describes what is happening but struggles to account for why or how we developed such abilities in the first place.

This opens the door to a similar idea as in morphic resonance or Meyer’s critique of neo-Darwinism: there may be an underlying intelligence or blueprint that cannot be reduced to mere chance or incremental improvements. Much like the Cambrian Explosion, universal grammar seems to signify a “jump” to a higher level of complexity that conventional evolutionary narratives do not fully address.

The Quranic Perspective: 30:22 and Beyond

From the viewpoint of the Quran—as translated by Rashad Khalifa—the suddenness and diversity we observe in nature aligns with a concept of intelligent design initiated by God. The Quran openly invites us to reflect on the creative power behind all that exists. A key verse often cited is 30:22, which states:

“Among His proofs are the creation of the heavens and the earth, and the variations in your languages and your colors. In these, there are signs for the knowledgeable.” (30:22)

This verse draws a direct connection between the majesty of cosmic creation and the variation in human languages and colors. Rashad Khalifa’s commentary highlights that these differences—much like the various life forms that emerged “explosively” in the Cambrian—are not the product of random chance but signs of a purposeful design. They are as remarkable and divinely orchestrated as the creation of the entire universe.

Other Quranic Threads Supporting a Guided Creation

Although 30:22 is a focal point for discussing linguistic and morphological variation, other verses in the Quran similarly highlight God’s deliberate act of creation. For instance, we find repeated references to God bringing the heavens and earth into being and orchestrating every aspect of existence. Rashad Khalifa consistently translated these passages to underscore the notion of a single, all-encompassing authority.

In Meyer’s and Sheldrake’s observations, we see hints of this same divine orchestration. The explosion of new body plans in the Cambrian period indicates a guiding power introducing vast amounts of information into the biosphere. Rupert Sheldrake’s “morphic fields” echo the Quranic insistence that there is more to life than we can physically measure—an unseen dimension that actively shapes outcomes. And Chomsky’s universal grammar model, while powerful in explaining the mechanics of language acquisition, may unwittingly point to a deeper, God-ordained blueprint for the gift of speech and communication, rather than simply a beneficial genetic mutation.

Converging on the Reality of Intelligent Design

Taken together, these perspectives—from Darwin’s doubts about the Cambrian Explosion, to Sheldrake’s morphic resonance, to Chomsky’s universal grammar, and finally to the Quranic worldview—suggest that intelligent design is an inescapable conclusion. The arguments do not deny the role of adaptation or variability within species; rather, they push us to think beyond the standard, purely materialistic frameworks.

Instead of viewing life’s complexity as a cobbled-together chain of accidental events, we might see it as a tapestry woven with intent—a reflection of a higher intelligence that seamlessly integrated new body plans (the Cambrian Explosion), collective biological memory (morphic resonance), and human linguistic capacity (universal grammar) into an intricately balanced world.

Submission and Recognizing the Source

Rashad Khalifa’s translation of the Final Testament encourages us to see these phenomena as proofs—direct evidence of an overarching intelligence that frames every corner of reality. In embracing submission to God (as taught in the Quran), we are called to acknowledge the Author behind these miracles.

Darwin’s struggle to reconcile the abruptness of the Cambrian Explosion with gradualist evolution, Sheldrake’s intuition about collective biological memory, and Chomsky’s postulation of innate grammatical structures each highlight gaps that point toward something greater than mere randomness. By integrating the Quranic perspective, we begin to see these gaps as signposts directing us toward a Creator—One who designed both the cosmic order and the myriad forms of life with wisdom and purpose.

As verse 30:22 reminds us, the creation of the heavens and the earth and the amazing variations in our languages and colors are signs for those who reflect. These signs challenge us to look beyond naturalistic explanations, to acknowledge that God is truly running everything—from the branching of phyla in the Cambrian Explosion to the deeply ingrained language faculties enabling us to share these insights.

Leave a comment