Introduction

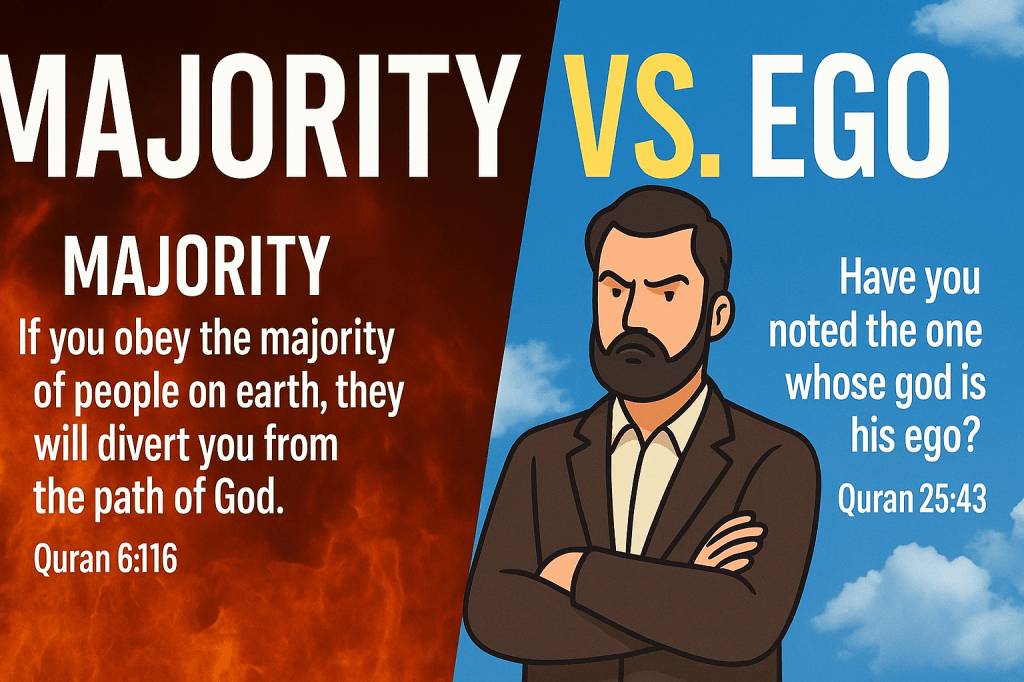

The Quran emphatically warns that truth is not determined by numbers. In fact, the majority of people are described as being misled and destined for failure if they persist in disbelief or idol worship. The Quran states:

[6:116] “If you obey the majority of people on earth, they will divert you from the path of God. They follow only conjecture; they only guess.”

At the same time, the Quran identifies the human ego (one’s own desires and opinions) as a false god that can lead one astray:

[25:43] “Have you seen the one whose god is his own ego? Will you be his advocate?”

These principles highlight a sobering reality: neither following the crowd nor following one’s self guarantees guidance. True salvation, according to the Quran, lies in obeying God by adhering to divine guidance — specifically, by recognizing and following His authorized messenger. In this context, that messenger is identified as Rashad Khalifa (1935–1990), who proclaimed to be a messenger of God and backed his claim with the discovery of the Quran’s mathematical code.

This article explores the Quranic evidence for these points: how “majority rule” can deceive, how ego and personal opinion become idols, and why the correct path is a third way distinct from both Sunni traditionalism and simplistic Quranism — namely, following God’s scripture and His messenger. We will also examine historical and scriptural evidence debunking the notion that one must follow Hadith (narrations) to obey the Prophet, providing a historical overview of how Hadith were compiled centuries after Prophet Muhammad, and demonstrating that the Quran was preserved independently of these narrations, as promised by God Himself.

The Deception of Following the Majority

One of the most repeated themes in the Quran is that majority opinion is not a reliable guide to truth. Believers are cautioned that just because an idea is popular or widely accepted does not make it correct. As we’ve seen above, the Quran states unequivocally in [6:116] that the majority would lead us away from God’s path. They base their beliefs on speculation and inherited ideas rather than confirmed knowledge.

In another verse, God tells Prophet Muhammad:

[12:103] “Most people, no matter what you do, will not believe.”

This is a clear indication that truth has never been determined by a democratic vote of mankind.

Indeed, the Quran goes so far as to reveal the tragic fate awaiting the majority of humanity:

[7:179] “We have committed to Hell multitudes of jinns and humans. They have minds with which they do not understand, eyes with which they do not see, and ears with which they do not hear. They are like animals; no, they are far worse – they are totally unaware.”

This verse paints a grim picture: countless people will end up in Hell because they failed to use the intellect and senses God gave them to recognize the truth. Like cattle, they merely follow the herd. In a similar vein, the Quran asks rhetorically:

[25:44] “Do you think that most of them hear, or understand? They are just like animals; no, they are far worse.”

Such verses confirm that blindly following societal norms or the religion of one’s forefathers can be spiritually lethal.

Crucially, the Quran also notes that even many who profess belief fall into error. A striking verse in the story of Joseph states:

[12:106] “The majority of those who believe in God do not do so without committing idol worship.”

In other words, most people who consider themselves “believers” still pollute their faith with some form of idolatry or false dependency. Whether it be reliance on saints, clergymen, ancestors’ ways, or other sources beside God, the masses are prone to shirk (associating partners with God).

Traditional Sunni Islam, with its heavy emphasis on following the consensus of the community and the voluminous traditions of the majority, falls squarely under this warning. By elevating the ummah’s consensus and the bulk of historical juristic opinions to the level of divine guidance, one risks following the crowd into what the Quran calls hidden idol worship.

Simply put, truth in Quranic terms is often upheld by a minority (the sincere believers), while the majority are “unaware” or in outright error.

The lesson is that a seeker of salvation must be willing to stand apart from the majority. Throughout history, God’s prophets and messengers often found themselves opposed by the masses. Noah was ridiculed by the majority; Abraham stood as an ummah (a nation) of one against his people’s idolatries; Lot’s values were rejected by most of his society. In each case, the Quran shows that numbers did not equate to legitimacy.

The criterion for truth is God’s guidance, not the popularity of an idea. Thus, a sincere Muslim should critically examine practices followed by the majority (such as the vast body of Hadith and sectarian doctrines in Sunni Islam) and ask: are these truly from God, or merely conjectures handed down by the many? The Quran’s guidance prepares us to resist “majority pressure” in matters of faith.

The Ego as a False God (Idolatry of the Self)

Opposite the error of slavishly following others is the error of arrogantly following one’s own ego. The Quran identifies the ego (vain desires) as a source of idolatry that can be just as dangerous as worshipping idols of stone. As noted earlier:

[25:43] “Have you seen the one whose god is his own ego? Will you be his advocate?”

When a person elevates hawa (personal whims or opinions) above God’s guidance, he has essentially made an idol out of himself. Quran 25:43 uses the striking phrase “whose god is his own ego,” implying that the ego can become a deity that one serves, consciously or not. Another verse in the same vein states:

[45:23] “Have you noted the one whose god is his ego? Consequently, God sends him astray, despite his knowledge, seals his hearing and his mind, and places a veil on his eyes. Who then can guide him, after such a decision by God? Would you not take heed?”

Here we learn that following one’s ego blinds a person to truth – it causes spiritual deafness and blindness as a punishment from God, because that person chose self over submission. No guidance can reach such a soul until they humble themselves and dethrone the ego.

Egoism is a subtle form of idolatry. While an idol-worshiper might bow to a statue, an ego-worshiper bows to his own self – prioritizing personal opinions or desires even when God’s evidence shows otherwise. The Quran considers this equally reprehensible.

It was ego (pride) that caused Satan to disobey God’s command to honor Adam; in effect, Satan idolized his own judgment (“I am better than him”) over God’s word. Humans fall into the same trap whenever they reject divine commandments in favor of personal preference. For example, a person who reads a clear injunction in the Quran but says “I’ll follow my own interpretation or comfort instead” is letting ego take precedence over God. The Quran warns that such an individual is left to wander astray, even if they possess knowledge, because arrogance has corrupted their heart.

In today’s context, “Quran-alone” or “Quranist” followers (those who rightly reject man-made Hadith, but then sometimes proceed to interpret the Quran purely on their own terms while dismissing any divinely guided teacher) are at risk of this ego-driven deviation. While they eschew the majority’s traditions, they may end up enthroning their personal opinion as the ultimate authority. They might refuse to acknowledge anyone else’s understanding or any messenger God sends, thinking that their own reading of the Quran is sufficient. This is a subtle form of ego-worship.

The Quran advocates following God’s guidance, not self-guidance. It tells us to remember God and seek refuge in Him precisely to avoid the ego’s tricks. In an Islamic worldview, one’s nafs (self) must be disciplined and submitted to God’s will; otherwise, it can become an ilāh (god) in its own right. We are reminded of the example of Prophet Muhammad, who, despite being God’s messenger, did not speak out of personal desire:

[53:3-4] “He does not speak on his own, it is but a revelation revealed.”

If even a messenger of God refrains from injecting personal ego into religion, how much more should ordinary believers be wary of their subjective whims.

Thus, the Quran sets up a clear contrast: On one side is idolatry of the majority – the comfort of following ancestral or popular traditions; on the other side is idolatry of the ego – the pride of following one’s own unsubmitted mind. Both are condemned. The straight path of Islam steers between these extremes: it requires the humility to break from the crowd when the crowd is wrong, and the humility to submit one’s ego to something higher than oneself. What is that higher authority? It is neither the masses nor the self, but God and the guidance He sends via His revelations and messengers.

Obeying God and His Messenger: The True Path to Salvation

If one neither blindly follows the many, nor one’s own self, what remains as a guide? The Quran’s answer is unambiguous: follow God’s guidance as brought by His messenger. Repeatedly, the scripture commands believers to “obey God and obey the messenger.” This obedience is the hallmark of the believers’ path, which distinguishes it both from anarchic individualism and from collective misguidance. For example, the Quran instructs Prophet Muhammad to proclaim to the people:

[24:54] “Say, ‘Obey God, and obey the messenger.’ If they refuse, then he is responsible for his obligations, and you are responsible for yours. If you obey him, you will be guided. The sole duty of the messenger is to deliver (the message).”

In this single verse, we find several key points:

- Obeying God and the messenger is required

- If people turn away, the messenger is only accountable for conveying the message, and we are accountable for our response

- Obeying the messenger is a means to guidance

- The messenger’s role is not to be a source of his own laws – his duty is only to faithfully deliver God’s message

From this we understand that obeying the messenger is nothing other than obeying God’s instructions as communicated through that messenger. Every messenger of God – Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, and others – brought specific revelations or commands from God. To obey those messengers was to obey God who sent them. Conversely, to reject a true messenger is to reject God’s guidance. The Quran makes this equivalence clear:

[4:80] “Whoever obeys the messenger is obeying God.”

The messenger is never to be set up as a rival to God; rather, the messenger is an emissary who leads people to God.

It follows that after Prophet Muhammad’s time, one cannot claim to be obeying God while disregarding the message he delivered – the Quran. Nor can one claim to obey Muhammad while disregarding God’s commands, since Muhammad’s entire mission was to convey God’s words, not his own. Traditional Sunni Islam often stresses “obey the Prophet” but then substitutes the Hadith literature for the actual message of the Prophet. As we will see later, obeying God’s messenger means upholding the revelation he brought (the Quran) and any guidance authenticated by God, not following unauthenticated stories.

In the contemporary period, Rashad Khalifa asserted that he was a messenger of God in accordance with Quranic prophecies. Specifically, he identified himself with the Messenger of the Covenant mentioned implicitly in Quran 3:81 (and in the Biblical book of Malachi). Rashad Khalifa’s mission was to purge Islam of innovations and restore pure monotheism. He famously discovered a mathematical structure in the Quran based on the number 19, which he presented as proof of the Quran’s miraculous preservation and his divine commission.

Accepting Rashad Khalifa as a messenger sent by God entails heeding his core message: worship God alone, uphold the Quran alone as the source of religious law, abandon idolization of Prophet Muhammad or scholars, and appreciate the miracle of 19 as God’s tool to authenticate the scripture. In practical terms, this means that salvation lies in obeying God’s commandments in the Quran and the guidance given through His messenger (which in Rashad’s case included exposing two false verses that had been added to the Quran, and clarifying Quranic practices free from distortion). It is a path that neither idolizes human tradition (the trap of the Sunni majority) nor idolizes one’s independent opinions (the trap of ego-driven “Quranism”), but rather submits to God’s authority as delivered by God’s chosen envoy.

Importantly, even Rashad Khalifa taught that no messenger brings anything outside of God’s revelations. He titled his English translation of the Quran “The Final Testament” to emphasize that the Quran is the last scripture and that his role was simply to confirm it and guide people to its proper understanding, not to add new doctrine. This aligns with the Quranic statement we saw in [24:54]: “The sole duty of the messenger is to deliver the message.” A messenger might explain or exemplify God’s message, but he never supplants it.

Thus, obeying Rashad as a messenger means following the Quranic path he championed, not treating him as an infallible object of worship. In Rashad’s case, “obeying the messenger” translates into implementing the Quran’s teachings (since he advocated Quran-alone Islam) and accepting legitimate divine guidance (such as the miraculous verification of the Quran through the code 19). It categorically does not mean accumulating a new corpus of Hadith around Rashad’s own sayings — a mistake that some of Prophet Muhammad’s followers fell into after his death, which led to the problems we will discuss. True obedience to God’s messengers always directs one to worship God alone and follow His scripture.

To summarize, the Quran delineates a third path distinct from both majority-rule religion and ego-based religion: it is the path of God’s revelations as taught by God’s messenger. In every age, those who find salvation are those who break with wrongful majority practices, suppress their personal caprices, and humbly obey the divine instructions brought by the messenger of their time. In the time of Muhammad, that meant adhering to the Quran he delivered and the inspiration he was given. In our time, it means adhering to the Quran (final scripture) and heeding the message of any subsequent Messenger of God’s Covenant who confirms that scripture.

Rashad Khalifa’s followers thus see themselves as neither “Sunni” nor “Quranist” in the conventional sense, but Submitters who follow the Quran with the benefit of God’s authorized messenger’s clarification. This approach is rooted solidly in Quranic verses that praise obedience to God and messenger while condemning loyalty to human conjectures or egos.

The Quran vs. Hadith: Does Obeying the Messenger Mean Following Hadith?

An important point of contention must be addressed: Sunni Islam holds that “obeying the Messenger” equates to following the Hadith and Sunna (the reported sayings and practices of Prophet Muhammad). Sunni scholars argue that the Quran alone is not enough, and that one must obey the Prophet’s instructions found in Hadith to truly obey God. They often cite Quranic verses such as “Obey Allah and obey the Messenger” to justify the authority of tens of thousands of Hadith reports compiled centuries after the Prophet. However, the Quran itself provides evidence that undermines this claim. Nowhere does the Quran say “obey God and obey the Hadith of the Prophet.” On the contrary, it strongly cautions against accepting any other guidance as a source of religion besides what God revealed.

First, God calls the Quran “fully detailed” and the only acceptable source of law for the believer:

[6:114] “Shall I seek other than God as a source of law, when He has revealed to you this book fully detailed?”

This rhetorical question makes it clear that no supplementary source (like Hadith) is needed for religious guidance, since God’s Book is complete in itself. The next verse affirms:

[6:115] “The word of your Lord is complete, in truth and justice.”

If the Quran is fully detailed and complete, then elevating Hadith as an additional necessary source is a tacit accusation that the Quran is insufficient – something a believer should shudder to imply. Sunni apologetics often respond that “fully detailed” refers only to broad principles, but this interpretation conflicts with the plain words of the verse. According to The Final Testament translation, God has deliberately made the Quran a complete guidance, and seeking religious laws from outside it (such as man-made narrations) is portrayed as seeking another lord besides God.

Furthermore, the Quran uses the term “Hadith” in a theological sense, and not in a favorable light:

[45:6] “These are God’s revelations that we recite to you truthfully. In which Hadith other than God and His revelations do they believe?”

This verse pointedly asks the reader to reflect – what other narrative or message will you follow, if not God’s own revelations? The word hadith here unmistakably means any talk or story about religion not authorized by God. Similarly, Quran 7:185 and 77:50 (among other verses) pose the challenge:

[77:50] “Which Hadith, other than this (Quran), do they uphold?”

These statements are incredibly relevant: they anticipate exactly the situation we see in Sunni Islam, where volumes of Hadith have effectively become a second source of guidance that can even override the Quran’s clear meaning. The Quran, centuries before Bukhari or Muslim, already warned Muslims not to fall into this trap of upholding other “hadiths” beside the divine Revelation. Obeying the messenger was never meant to be an excuse to obey unauthorized texts compiled long after the messenger. It meant obeying the message he delivered – for Muhammad, that was the Quran.

Sunni scholars will counter: “But the Quran tells us to obey the Prophet’s commands, and those commands are recorded in Hadith.” They often quote the Prophet’s reported sayings like “Take what I have given you and abstain from what I forbid” (a hadith) to justify binding Hadith. Yet this reasoning is circular: it uses Hadith to justify following Hadith. The Quranic evidence reveals a different picture. As mentioned, Quran 24:54 shows the messenger’s role was only to convey the message; it does not endorse following every reported action or saying attributed to the Prophet. In fact, the Quran even predicts the phenomenon of Hadith fabrication and urges the Prophet to judge by the Quran alone:

[5:48] “We have revealed to you this Scripture, truthfully, confirming previous scriptures, and superseding them. So judge between them according to what God has revealed, and do not follow their wishes if they differ from the truth that came to you.”

This underscores that the Prophet’s source of judgment was what God revealed (the Quran), not people’s wishes or unverified reports.

Historically, it is documented that Prophet Muhammad prohibited writing down his sayings in his lifetime, specifically to prevent confusion between the Quran and other material. Early caliphs such as Abu Bakr and Umar followed this policy by discouraging or outright banning the collection of Hadith, fearing that a secondary authority would emerge alongside the Quran. This is consistent with Quranic logic: God’s Word must remain sole and supreme.

The absence of hadith documentation in Islam’s first generation shows that the companions of the Prophet themselves did not equate “obey the messenger” with compiling and following a library of hadith. Rather, “obey the messenger” meant obeying the living Prophet in his lifetime – when he could personally guide the community with God’s inspiration – and, after his death, it meant obeying the message he left behind (the Quran).

Sunni Islam’s claim that obeying Hadith = obeying the Prophet is further refuted by observing the content of many Hadith. If a hadith contradicts the Quran, or paints an un-Quranic image of the Prophet, following it would actually make one disobey God and His messenger. For example, the Quran emphasizes that Muhammad was a man of exemplary character who preached mercy and reason. Yet some sahih (authentic) hadiths depict him saying extremely harsh things (like advocating execution for trivial matters, or cursing people) that clash with Quranic ethos. Which do we obey in such cases – the Quran’s portrayal or the hadith report? The Quran’s answer is clear: no “Hadith” should be accepted if it’s not from God. The messenger’s true teachings can never conflict with God’s scripture. Thus, if there is a conflict, the fault lies in the man-made narration, not in the messenger. By sticking to the Quran, we are sure to be obeying the Prophet’s genuine teachings, since he never taught anything contrary to the Quran.

In summary, obeying the messenger Muhammad today means to uphold the Quran alone as your guidance, as that is the verified message he delivered and lived by. The Sunni insistence that one must follow thousands of Hadith to obey the Prophet has no basis in the Quran. On the contrary, the Quran equips the believer to reject this claim: it calls itself “fully detailed”, asks “in what Hadith after God and His verses will you believe?”, and reminds us that the Messenger’s duty was only to deliver the clear message.

Any devout Muslim who takes these Quranic verses seriously will conclude that Hadith are not a divine requirement. Respecting and loving the Prophet does not mean collecting unverifiable quotes attributed to him and treating them as sacred; it means following his actual legacy, the Quran, and any confirmed guidance from God. Ironically, Sunni traditionalists who heavily emphasize “obey the Messenger” have, according to Quranic criteria, deserted the Messenger’s message by upholding man-made books. This fulfills the warning in Quran 25:30, where the Messenger will complain on the Day of Judgment:

[25:30] “My Lord, my people have deserted this Quran.”

One form of desertion is replacing the Quran with sectarian lore. True adherence to Muhammad requires returning to the Quran and abandoning the idolatry of Hadith literature – an idolatry of both the majority’s tradition and of venerating the Prophet beyond what God authorized.

The Emergence of Hadith Literature: Late Compilation and Motives

To further appreciate why Hadith should not be treated as equal to the Quran, it is instructive to review the history of Hadith compilation. Far from being diligently recorded in the Prophet’s life or immediately after, Hadith literature arose much later, under specific historical and political circumstances. This fact is acknowledged by Muslim scholars and orientalists alike.

According to historical research, Hadith were not promptly written down during Muhammad’s lifetime or immediately after his death. Instead, they were documented several centuries after the time of Muhammad (Sunni sources, approximately 200-300 years after his death) and attributed to Muhammad through chains of narrators. In other words, the sayings now known as Hadith entered written form roughly in the 8th and 9th centuries CE, whereas Prophet Muhammad died in 632 CE. For over a hundred years, the Muslim community functioned without any canonical Hadith collections. Their focus was on the Quran, and for practical matters they relied on the Prophet’s immediate teachings remembered by senior companions, the decisions of the first caliphs, and local practices. There was no dense library of written Hadith in the first generation of Islam.

Historical records indicate that the early caliphs were extremely cautious about Hadith. It is reported (in traditional Muslim sources themselves) that the first four Caliphs – Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali – all discouraged the excessive narration of the Prophet’s sayings and banned the writing of Hadith. Caliph Umar in particular is said to have warned people not to start writing down quotes lest Muslims deviate from the Quran. This policy resulted in very few hadiths being systematically recorded in the 7th century.

There were isolated personal notebooks (such as one companion, Ibn Amr, who wrote some sayings with the Prophet’s permission), but these were not widely circulated, and many were lost or absorbed into later compilations. Muslim historians concede that no authoritative hadith book from the first century AH (after Hijra) has survived; even the early snippets known (like the Sahifa of Hammam ibn Munabbih) were essentially family notes, not a public reference, and their texts are preserved only through later copies.

There is a “general consensus among hadith scholars that it was in accordance with the forbiddance of hadith writing by early Islam” that we see “no authoritative hadith book during the first two centuries of Islam.” Only as this strict stance gradually relaxed did hadiths begin to be transmitted more freely – unfortunately accompanied by a great deal of oral fabrication.

By the second Islamic century (8th century CE), the Muslim world had expanded vastly, and new generations, no longer personally acquainted with the Prophet or his companions, began to feel a need for more detailed guidance. This coincided with the rise of various sects and schools of thought, each seeking validation. It is in this milieu that Hadith narration blossomed – for both genuine and spurious reasons.

Scholars like Imam Malik in Medina compiled sayings and judgements of the Prophet’s companions and a few prophetic hadiths into works like the Muwatta’ (circa mid-8th century). But these were regionally limited and relatively small. As time went on, more people started collecting whatever reports they could find about the Prophet. By the mid-9th century, the famous canonical collections were compiled: Sahih al-Bukhari, Sahih Muslim, and others (Abu Dawud, Tirmidhi, Nasa’i, Ibn Majah) in Sunni Islam. Imam al-Bukhari, perhaps the most renowned hadith compiler, died in 870 CE – over two centuries after Prophet Muhammad.

By the time Bukhari and Muslim undertook their collections, the amount of material in circulation was enormous – and problematic. Muslim historians openly admit that many false attributions had been made to the Prophet in the intervening centuries. Bukhari reportedly examined 600,000 narrations, out of which he accepted only about 7,000 (including repeats) as sufficiently authentic. In other words, over 99% of what people were quoting as “Prophet said…” was deemed inauthentic or unreliable by Bukhari’s own criteria. This stunning ratio underscores how pervasive fabrication and error had become.

It is recorded that early hadith scholars would travel long distances to cross-examine narrators, only to find that many hadiths were outright forgeries or too weak to trust. Imam Muslim and others performed similar filtering. The compilers had to sort through “mountainous piles of individual hadith reports”, as one source describes, only retaining a tiny fraction. This reality should give any Muslim pause: if Hadith were meant to be a crucial part of the faith, why did God allow so much confusion and forgery to surround them, in contrast to the Quran which was preserved so meticulously?

The outcome of the hadith collection process is that six books (Kutub al-Sittah) became canon in Sunni Islam, containing around 20,000 distinct hadiths among them. But even these books are not free from contradictions and questionable content; they are simply the best that could be done given the circumstances.

What drove the massive proliferation of hadiths in those first 200 years? Historians identify several motives:

- Political motives: After the Prophet’s death, leadership disputes and dynastic struggles plagued the Muslim community. Partisans on all sides generated hadith to support their claims. For instance, during the Umayyad vs. Abbasid conflict, or Sunni vs. Shi’a disputes, each side produced “prophetic” statements bolstering their legitimacy. The Abbasids, when in power, sponsored scholars like Bukhari; they had an interest in standardizing Islam in a way that cemented their rule. A hadith even appeared predicting “12 caliphs all from Quraysh,” conveniently matching the early caliphs and perhaps Abbasid hopes. Another hadith would praise the city of Baghdad (the Abbasid capital) implicitly. In short, rulers and factions used hadith as a propaganda tool. The number of hadiths began “multiplying in suspiciously direct correlation to their utility” to the quoter. Traditionists produced hadiths warning against listening to human reason (aimed at undermining rationalist Muslims), while rival jurists produced hadiths extolling their founders. The existence of such politically or ideologically motivated forgeries is acknowledged even in orthodox Muslim scholarship.

- Sectarian/Scholarly motives: As legal schools (Hanafi, Maliki, etc.) and theological debates arose, hadiths were often cited to back each position. Initially, as Professor Joseph Schacht and Ignaz Goldziher observed, the earliest generations of jurists (7th–early 8th century) did not use prophetic hadith much at all. They preferred to base rulings on the Quran, and the precedent of the companions. However, by the late 8th century, there was a “gradual infiltration and incorporation of Prophetic hadiths into Islamic jurisprudence.” Scholars found that claiming the Prophet said something was a powerful way to legitimize a practice. Goldziher famously concluded that many hadiths were “statements attributed to the Prophet by later generations to support their own views”. In response to this chaotic situation, Imam al-Shafi’i (d. 820 CE) championed the idea that the Prophetic Sunna, known through hadith, must be accorded equal authority to the Quran. This was a turning point: it theoretically justified using hadith to settle debates. But to make this meaningful, they had to distinguish authentic from fake – hence the elaborate science of isnad (chains of narrators) criticism was developed. Still, as noted, the sheer volume of material meant that many hadiths slipped through that were products of their time, not true utterances of Muhammad.

- Popular piety and story-telling: Apart from power and polemics, some hadiths arose simply from the human love of stories. Storytellers (qussas) would embellish tales of the Prophet and his companions to inspire the masses. Without ill intent, people might pass on a morally edifying tale that wasn’t factual. Over generations, these too became “hadith.” Sufi mystics, focusing on spirituality, contributed sayings about inner devotion or miracles that entered hadith corpora. Good intentions, however, do not equate to authenticity.

The net effect of these factors was that by around 250 AH (circa 870 CE), a huge corpus of Hadith was circulating, out of which only a small percentage could be verified with any confidence. The hadith scholars did the Muslim world a service by eliminating the most egregious fabrications and organizing the material. But even the best collections (like Bukhari’s) reflect the biases and limitations of their era. They were, after all, compiled in an Abbasid imperial context, in Persian and Iraqi cities far from Arabia, in a milieu where Islam had absorbed influences from converted peoples. Many authentic prophetic sayings may have been lost, and conversely, some inauthentic ones might have been unknowingly accepted. Sunni Islam eventually canonized these collections and treated them – functionally – as the second half of revelation. But as we have shown in the previous section, this contradicts the Quran’s injunction that God’s revelations (the Quran itself) are complete and should not be supplemented by conjectures.

Understanding this history helps clarify that obeying God and His messenger cannot simply mean embracing the Hadith literature wholesale. If God intended the Prophet’s sayings to be perfectly preserved for all time as a requirement for the faith, then the 200+ year gap, the massive outbreak of forgeries, and the often dubious content of even “sahih” hadiths are inexplicable. A more reasonable view — which the Quran itself supports — is that authentic Sunna (practice) of the Prophet was passed down primarily in the form of living tradition (e.g. how to perform the Contact Prayers, which Muslims learned by communal practice), and the Quran was always meant to be the sole textual criterion for faith. The compiled Hadith books, while containing some wisdom, are not infallible sources and were never mandated by God as part of the religion. They were a later human attempt at preserving memory, subject to error.

Leave a comment