Introduction: The Foundation of Faith

The Quran presents itself as complete, fully detailed, and sufficient for guidance. Yet traditional Sunni Islam has built an entire parallel system of authority around the hadiths—oral traditions attributed to the Prophet Muhammad. Among all hadith narrators, none is more prolific or more problematic than Abu Hurairah, a man who reportedly transmitted 5,374 hadiths despite spending only 3-4 years with the Prophet.

When we examine the numbers, the historical record, and the criticisms leveled by the Prophet’s own companions, a disturbing pattern emerges. This isn’t about attacking a historical figure—it’s about protecting the integrity of our faith from fabrications that contradict the Quran itself. The evidence against Abu Hurairah’s reliability isn’t speculation or sectarian bias. It’s mathematical impossibility, documented imprisonment for corruption, and direct accusations from those who knew the Prophet far better than he did.

[6:114] “Shall I seek other than God as a source of law, when He has revealed to you this book fully detailed? Those who received the scripture recognize that it has been revealed from your Lord, truthfully. You shall not harbor any doubt.”

The Quran explicitly states it is fully detailed. So why has Abu Hurairah’s massive hadith collection become a second source of law, often contradicting or adding to what God has already completed?

Part 1: The Statistical Impossibility

The Numbers That Don’t Add Up

Abu Hurairah converted to Islam in 7 AH (628 CE) and the Prophet died in 11 AH (632 CE). This gives a maximum association period of 4 years, though most scholars acknowledge it was closer to 3 years. During this brief time, Abu Hurairah allegedly memorized and transmitted 5,374 hadiths—more than any other companion.

To put this in perspective: Abu Bakr, the Prophet’s closest friend who spent 23 years with him, narrated only 142 hadiths. Umar, who spent similar time and was known for his exceptional memory, narrated 537 hadiths. Aisha, the Prophet’s wife who lived with him for 9 years, narrated 2,210 hadiths. Yet Abu Hurairah, with his 3-4 year association, narrated 38 times more than Abu Bakr and 10 times more than Umar.

The mathematics are stark. If we assume 4 years (the maximum possible), Abu Hurairah would need to have heard, memorized, and later transmitted approximately 3.7 new hadiths every single day, without exception, for four straight years. If we use the more realistic 3-year timeframe, this jumps to 4.9 hadiths per day. This assumes the Prophet spent every single day teaching Abu Hurairah new material, with no repetition, no days of travel, illness, or other activities.

Compare this to Abu Bakr’s 142 hadiths over 23 years—an average of 6.2 hadiths per year, or one new hadith every 59 days. Which scenario seems more plausible? That the Prophet’s daily companion for 23 years heard only 142 unique narrations worth preserving, or that a latecomer absorbed nearly 5,400 in a fraction of the time?

Part 2: Umar’s Imprisonment and Beating

When the Caliph Called Out Corruption

The statistical anomaly alone should raise questions. But the historical record provides even more damning evidence. During the caliphate of Umar ibn al-Khattab—the second caliph and one of Islam’s most respected figures—Abu Hurairah was appointed governor of Bahrain. What happened next is documented in multiple classical Islamic sources and is devastating to Abu Hurairah’s credibility.

According to Ar-Riyad an-Nadira by at-Tabari and confirmed in Kitab al-Amwal by Abu Ubayd, Umar discovered that Abu Hurairah had embezzled 10,000 dirhams from the public treasury. When Abu Hurairah returned to Medina, Umar confronted him publicly and, according to the historical accounts, beat him with his walking stick until he bled. Umar then stripped him of his governorship and confiscated the stolen money.

But here’s what makes this particularly relevant to the hadith issue: Umar didn’t just accuse Abu Hurairah of theft. He explicitly accused him of narrating too many hadiths and fabricating traditions. The sources record Umar’s words: “You narrate hadiths that we never heard while we were with the Messenger of God.” This wasn’t just about financial corruption—it was about religious corruption, about inventing traditions that the most senior companions had never heard.

Ibn Qutaybah’s *Ta’wil Mukhtalif al-Hadith* records that Umar threatened Abu Hurairah: “You must stop narrating hadiths about the Messenger of God, or I will exile you to the land of Daws” (Abu Hurairah’s home tribe). Think about what this means: the Caliph of Islam, a man known for his fierce commitment to truth and justice, threatened to exile someone for narrating too many “hadiths.” Why would he do this unless he believed those hadiths were fabrications?

Traditional scholars try to soften this incident, claiming Umar was just being cautious or that the beating was a misunderstanding. But the sources are clear: embezzlement, beating until bloodshed, confiscation of funds, removal from office, and explicit threats to stop narrating. This is not the treatment of a trustworthy narrator. This is the treatment of a corrupt official and a suspected fabricator.

[17:36] “You shall not accept any information, unless you verify it for yourself. I have given you the hearing, the eyesight, and the brain, and you are responsible for using them.”

God commands us to verify information. When the second Caliph of Islam verifies Abu Hurairah and finds him corrupt both financially and narratively, shouldn’t we take that verification seriously?

Part 3: Aisha’s Devastating Corrections

The Prophet’s Wife vs. The Professional Narrator

If Umar’s accusations weren’t enough, we have the testimony of Aisha, the Prophet’s wife who spent nine years in his household. The classical sources preserve multiple instances where Aisha directly contradicted and corrected Abu Hurairah’s narrations, often in harsh terms.

In one famous incident recorded in *Sahih Muslim* and other collections, Abu Hurairah narrated that the Prophet said a bad omen can be found in a woman, a home, or a horse. When Aisha heard this, she was furious. She said: “Abu Hurairah has misunderstood what he heard. The Prophet was explaining what the people of Jahiliyyah (pre-Islamic ignorance) used to believe. He never said these things contain bad omens himself.”

This is significant because it reveals Abu Hurairah’s methodology: he would hear part of a conversation, misunderstand the context, and then narrate it as if the Prophet was making a definitive statement. How many of his 5,374 hadiths suffer from the same problem? How many are fragments taken out of context, or worse, complete fabrications?

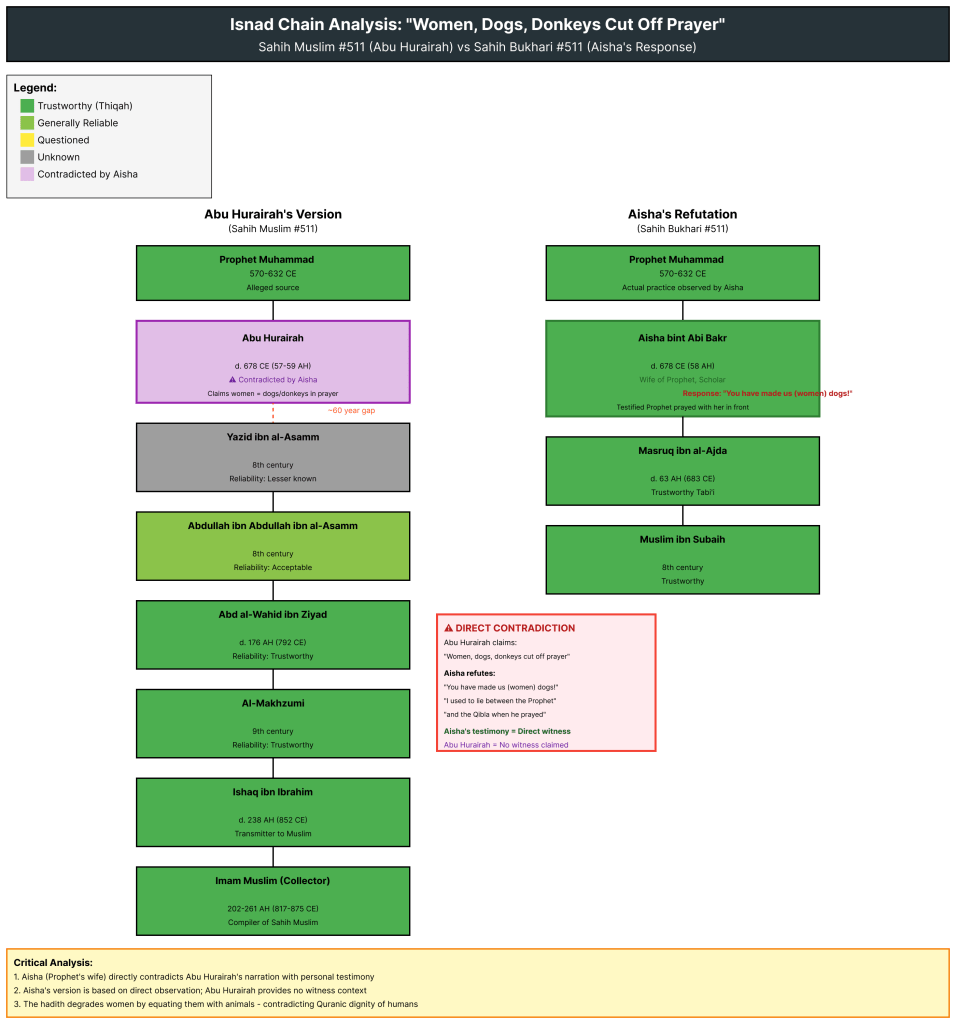

In another instance, Abu Hurairah claimed the Prophet said that prayer is invalidated if a woman, a donkey, or a dog passes in front of the person praying. Aisha’s response, preserved in multiple sources, was scathing: “You have made us equal to donkeys and dogs! By God, I saw the Prophet praying while I was lying on the bed between him and the qibla, and I would get up when I needed something.”

Notice what Aisha is doing here: she’s not just correcting a minor detail. She’s exposing Abu Hurairah as someone who narrates things that contradict her direct, lived experience with the Prophet. She lived with him. She saw his daily practice. And what Abu Hurairah claims contradicts what she witnessed firsthand. Who should we trust: the woman who spent nine years in the Prophet’s household, or the latecomer who spent 3-4 years and has already been accused of fabrication by the Caliph?

The pattern continues. Classical sources record Aisha correcting Abu Hurairah on matters of ritual purity, inheritance, and various legal rulings. In many cases, she doesn’t just say he’s wrong—she questions his honesty. One narration records her saying: “How bold Abu Hurairah is!” in response to one of his questionable hadiths. In the Arabic, this is a polite way of calling someone a liar.

Part 4: Ali’s Direct Accusation

The Prophet’s Cousin Calls Him a Liar

Perhaps the most damning testimony comes from Ali ibn Abi Talib, the Prophet’s cousin, son-in-law, and fourth Caliph. Ali was raised by the Prophet from childhood and spent his entire life in close companionship with him. His knowledge of the Prophet’s teachings was considered unparalleled among the companions.

Ibn Abul-Hadeed’s *Sharh Nahjul-Balagha*, a classical commentary on Ali’s sermons, preserves Ali’s statement about Abu Hurairah. Ali reportedly said: “The greatest liar among people—or he said, among the living—concerning hadith is Abu Hurairah ad-Dawsi.” In another narration, Ali’s words are even more direct: “The most lying of the people against the Messenger of God is Abu Hurairah.”

This is not a subtle criticism. This is not a gentle disagreement about interpretation. The Prophet’s cousin, a man known for his uncompromising commitment to truth, explicitly labels Abu Hurairah as the biggest liar regarding hadith. Let that sink in. The fourth Caliph of Islam, one of the ten companions promised Paradise according to Sunni tradition, calls Abu Hurairah a liar.

Traditional scholars have tried for centuries to explain away this statement, claiming it’s from unreliable sources or that Ali was speaking hyperbolically. But the narration appears in classical Sunni sources, and Ibn Abul-Hadeed—himself a respected scholar—presents it matter-of-factly. Even if we assumed Ali was exaggerating for rhetorical effect (which seems unlikely given his character), why would he single out Abu Hurairah at all unless there was a serious credibility problem?

The Tabaqat literature (biographical dictionaries of early Muslims) also preserves tensions between Ali and Abu Hurairah. When Ali became Caliph, Abu Hurairah notably distanced himself and later sided with Muawiyah during the civil war. This political alignment becomes important when we consider the next part of our investigation.

[53:28] “They had no knowledge about this; they only conjectured. Conjecture is no substitute for the truth.”

How many of Abu Hurairah’s 5,374 hadiths are based on conjecture, misunderstanding, or political motivation rather than actual knowledge? When the people who knew the Prophet best—his wife, his cousin, his closest companions—question his reliability, we must take that seriously.

Part 5: The Muawiyah Connection

Political Corruption and Hadith Fabrication

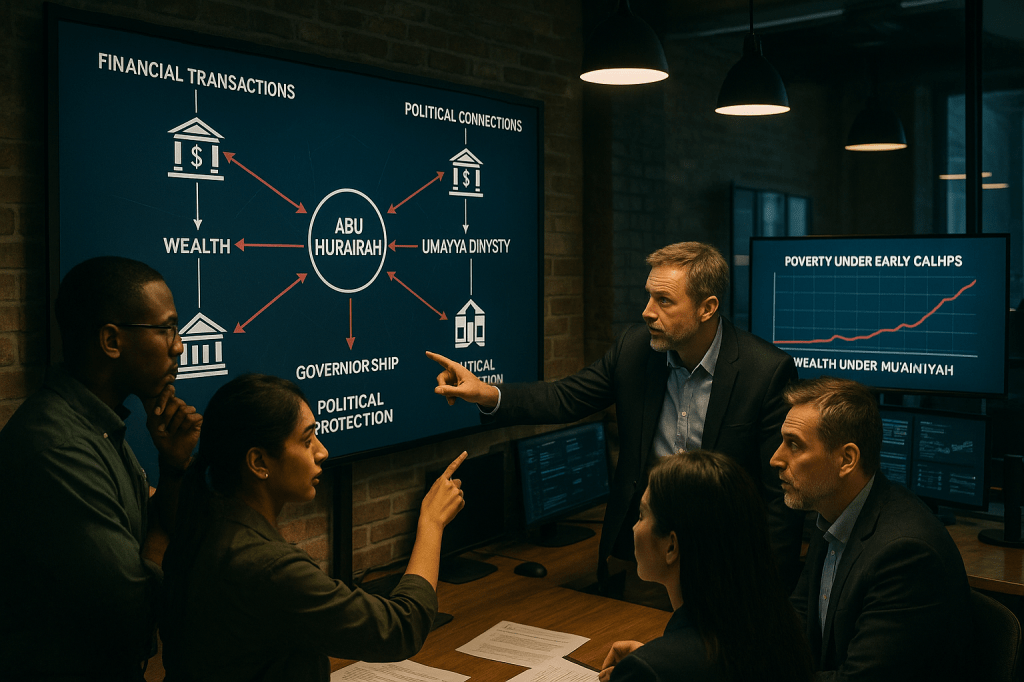

After Ali’s assassination, Abu Hurairah became closely aligned with Muawiyah ibn Abi Sufyan, the founder of the Umayyad dynasty. This wasn’t just a casual political preference—it was a lucrative partnership. Historical sources confirm that Muawiyah appointed Abu Hurairah as governor of Medina and showered him with wealth and property.

The Umayyad dynasty had a vested interest in legitimizing their rule through religious authority. They needed hadiths that supported monarchical succession, that elevated certain companions over others, and that provided religious justification for their political decisions. Abu Hurairah, with his massive and conveniently timed hadith repertoire, was the perfect tool.

Scholars have long noted that many of Abu Hurairah’s hadiths serve Umayyad political interests. Hadiths that emphasize obedience to rulers, that elevate the status of the Quraysh tribe (Muawiyah’s tribe), and that diminish the role of the Prophet’s family (Ali’s lineage) are disproportionately found in Abu Hurairah’s narrations. This is not coincidence—it’s systematic political manipulation of religious tradition.

Consider the timing: Abu Hurairah lived in relative poverty during the caliphates of Abu Bakr, Umar, and Ali. But under Muawiyah, he suddenly became wealthy and influential. What changed? His hadith narrations became politically useful. The man who Umar had beaten for embezzlement was now being rewarded by a dynasty that needed religious legitimacy.

This raises a critical question about the isnad (chain of narration) system that Sunni scholars rely on to validate hadiths. Abu Hurairah is the sole source for hundreds of hadiths. His students, who compiled these narrations decades after the Prophet’s death, had no way to verify them except by trusting Abu Hurairah’s word. And as we’ve seen, his word was questioned by those who had far better knowledge of the Prophet’s teachings.

The SVG diagrams below illustrate these problematic chains of narration, showing how single-source hadiths from a politically compromised narrator became foundational to Islamic law.

Visual Evidence: Abu Hurairah’s Problematic Isnad Chains

1. Moses Punches Angel of Death – Abu Hurairah’s Absurd Hadith

2. Women/Dogs/Donkeys Prayer Hadith – Aisha’s Direct Eyewitness Refutation

3. Abu Hurairah’s Self-Authenticating “Magical Memory Cloak” Claim

These isnad visualizations expose the core problems with Abu Hurairah’s hadiths: The Moses hadith shows him as the sole narrator of an absurd story contradicting Quranic theology. The women/dogs/donkeys hadith reveals direct contradiction by Aisha’s eyewitness testimony—she literally saw the Prophet pray while she lay between him and the qibla, disproving Abu Hurairah’s claim entirely. Most damning is the “magical memory cloak” hadith where Abu Hurairah authenticates himself through a private “miracle” that only he witnessed, conveniently explaining his statistically impossible narration count. These chains reveal a pattern: weak links, time gaps spanning decades, absurd content, and circular self-validation from a narrator already accused of corruption and fabrication by the most senior companions.

Part 6: Ibn Lahi’ah – The Burned Books Narrator

Weak Links in the Chain

Even if we were to give Abu Hurairah the benefit of the doubt, the chains of narration that transmit his hadiths are riddled with problematic narrators. One of the most significant is Abdullah ibn Lahi’ah, a narrator who appears in the isnad of numerous Abu Hurairah hadiths.

Classical hadith critics identified several fatal flaws with Ibn Lahi’ah. First, his library—containing his hadith notes and manuscripts—was destroyed in a fire. After the fire, he attempted to narrate hadiths from memory, but scholars noted that his memory had deteriorated significantly. He began confusing narrations, mixing up chains, and making errors.

Second, Ibn Lahi’ah was known for practicing tadlis (concealment of weak narrators in the chain). He would sometimes omit problematic links in the chain of narration to make a hadith appear stronger than it actually was. Third, later in life, he suffered from mental deterioration, yet he continued to narrate hadiths. Scholars noted that narrations from his later period are particularly unreliable.

Despite these well-documented problems, Ibn Lahi’ah appears in the chains of many Abu Hurairah hadiths that are used to establish legal rulings and theological doctrines. Why? Because without these weak chains, even fewer of Abu Hurairah’s narrations would be considered acceptable by classical standards.

This illustrates a broader problem: the entire hadith authentication system is built on circular reasoning. Abu Hurairah is considered reliable despite the accusations of Umar, Ali, and Aisha because later scholars needed his hadiths to support their legal schools. And narrators like Ibn Lahi’ah are given more credibility than they deserve because they’re essential links to Abu Hurairah’s massive collection.

[10:36] “Most of them follow nothing but conjecture, and conjecture is no substitute for the truth. God is fully aware of everything they do.”

When our religious law depends on narrators with burned books and failing memories, transmitting traditions from a man accused of fabrication by the Prophet’s own family, how can we claim to be following truth rather than conjecture?

Part 7: Absurd Hadiths Catalog

When Narrations Defy Reason and Revelation

Perhaps the strongest evidence against Abu Hurairah is the content of many hadiths attributed to him. These narrations don’t just contradict the Quran—they contradict basic reason, scientific understanding, and the dignity of God’s prophets.

Consider the hadith where Abu Hurairah claims Moses punched the Angel of Death and knocked out his eye. According to this narration, Moses was so strong that he physically assaulted an angel and damaged him. The angel had to return to God to get his eye restored. This absurd story raises immediate questions: Can angels be physically harmed? Would a prophet of God attack a divine messenger? Does God send angels on missions without warning His prophets first?

Then there’s the hadith claiming that Satan spends the night in your nose, and you should rinse your nose upon waking to expel him. This narration has led to elaborate explanations by classical scholars about Satan’s nature and size. But the simpler explanation is that it’s nonsense—a folk superstition dressed up as religious teaching.

Abu Hurairah narrated that yawning comes from Satan, and that Satan laughs when you yawn. He narrated that the Prophet said to kill black dogs specifically because they are devils. He narrated that women, dogs, and donkeys invalidate prayer if they pass in front—a hadith that Aisha explicitly refuted as we discussed earlier.

One particularly problematic hadith claims that God created Adam 60 cubits tall (approximately 90 feet), and humans have been decreasing in size ever since. This contradicts all archaeological and paleontological evidence about human evolution and stature. But it’s accepted in traditional Sunni theology because it comes from Abu Hurairah.

These aren’t minor details about prayer timing or dietary preferences. These are fundamental claims about the nature of reality, the character of prophets, and the workings of the spiritual world. And they contradict both the Quran and observable reality. The Quran presents prophets as wise, dignified human beings, not as cartoon characters punching angels. The Quran presents Satan as a spiritual tempter, not a physical being residing in nostrils.

When we combine these absurd narrations with the mathematical impossibility of his narration volume, the accusations from senior companions, and his political corruption, a clear picture emerges: Abu Hurairah was, at best, careless with truth, and at worst, a deliberate fabricator who capitalized on his narrations for political and financial gain.

Part 8: The Quranic Refutation

God’s Complete Revelation vs. Man’s Additions

Ultimately, the Abu Hurairah problem isn’t just about one narrator’s credibility. It’s about a fundamental question: Is the Quran complete and sufficient, or do we need thousands of additional narrations to understand God’s will?

[6:38] “All the creatures on earth, and all the birds that fly with wings, are communities like you. We did not leave anything out of this book. To their Lord, all these creatures will be summoned.”

God explicitly states that nothing was left out of His book. Not “nothing important” was left out. Not “most things” are in the book. Nothing was left out. This verse alone should end the debate about whether we need hadith collections to supplement the Quran.

[6:115] “The word of your Lord is complete, in truth and justice. Nothing shall abrogate His words. He is the Hearer, the Omniscient.”

The word is complete. Not partial, not incomplete without oral traditions, not requiring supplementation from Abu Hurairah or anyone else. Complete. In truth and justice. Nothing abrogates it—not hadith, not consensus, not the opinions of scholars.

[16:89] “The day will come when we will raise from every community a witness from among them, and bring you as the witness of these people. We have revealed to you this book to provide explanations for everything, and guidance, and mercy, and good news for the submitters.”

Explanations for everything. Not some things. Everything. The Quran provides guidance, mercy, and good news. It doesn’t say “the Quran plus authentic hadiths collected 200 years later provide guidance.” It says this book—the Quran—provides explanations for everything.

Traditional scholars argue that we need hadith to understand how to perform the contact prayers (salat), how to calculate zakat, and other practical matters. But this argument assumes the Quran is unclear about these matters, which contradicts its own self-description as clear and detailed. Moreover, it ignores that the prayer and zakat were practiced by entire communities before hadith books were compiled. These practices were passed down through living tradition, not through the narrations of someone who Umar beat for fabrication.

[39:23] “God has revealed herein the best Hadith; a book that is consistent, and points out both ways (to Heaven and Hell). The skins of those who reverence their Lord cringe therefrom, then their skins and their hearts soften up for God’s message. Such is God’s guidance; He bestows it upon whomever He wills. As for those sent astray by God, nothing can guide them.”

God calls the Quran “the best Hadith.” Not “a good hadith that needs supplementation by Abu Hurairah’s 5,374 narrations.” The best. The implication is clear: other hadiths are inferior, unnecessary, and potentially misleading.

[45:6] “These are God’s revelations that we recite to you truthfully. In which Hadith other than God and His revelations do they believe?”

This verse is devastating to hadith-based theology. God asks: in which hadith other than His revelations do they believe? The question is rhetorical, implying that belief in other hadiths is misguided. Yet traditional Islam has built an entire parallel legal system based on precisely that—believing in hadiths other than God’s revelations.

The Abu Hurairah problem exposes the fundamental flaw in traditional Sunni methodology. By elevating hadith collections to the status of secondary revelation, and by defending problematic narrators like Abu Hurairah because rejecting them would collapse the entire system, traditional Islam has created a house of cards built on conjecture rather than certainty.

Part 9: Why This Matters Today

The Real-World Consequences of Bad Narrations

Some might argue that historical debates about Abu Hurairah’s reliability are academic exercises with no practical importance. They couldn’t be more wrong. The hadiths attributed to Abu Hurairah have shaped Islamic law, social practices, and theological understanding for 1,400 years. And many of these influences are deeply harmful.

Consider the hadith about women, dogs, and donkeys invalidating prayer. Despite Aisha’s explicit refutation, this narration has been used to justify the inferior treatment of women in Islamic discourse. Women are grouped with animals as sources of spiritual contamination. The psychological and social impact of such teachings cannot be overstated.

Abu Hurairah’s narrations are frequently cited in contemporary debates about women’s rights, religious authority, and Islamic law. His hadiths are used to justify limiting women’s testimony in court, restricting their public roles, and treating them as inherently deficient in religious practice. Yet these narrations come from a man who was beaten by the Caliph for corruption and called a liar by the Prophet’s cousin.

The hadith about killing black dogs has led to animal cruelty justified in religious terms. The narration about Satan in the nose has made Islam seem primitive and superstitious to modern audiences. The claim about 90-foot tall Adam has put Muslim apologists in the impossible position of defending pseudoscience.

More broadly, the reliance on Abu Hurairah’s hadiths has diverted Muslims from the Quran’s actual message. Instead of focusing on the Quran’s emphasis on reason, justice, compassion, and direct relationship with God, traditional Islam has become obsessed with minute details of ritual purity, legalistic hair-splitting, and defending narrations that contradict both revelation and reason.

The Quran calls for using our God-given reason. It repeatedly emphasizes thinking, reflecting, and observing the natural world. But when we accept Abu Hurairah’s absurd narrations as religious truth, we’re forced to abandon reason and embrace blind following. We’re told that scholarly consensus and chain authentication are more important than obvious contradictions and mathematical impossibilities.

[17:36] “You shall not accept any information, unless you verify it for yourself. I have given you the hearing, the eyesight, and the brain, and you are responsible for using them.”

This verse makes us individually responsible for verification. We cannot outsource our critical thinking to medieval scholars who had their own political and sectarian biases. We cannot accept information just because it appears in Bukhari or Muslim’s collections. We must verify for ourselves—and when we do, Abu Hurairah’s narrations collapse under scrutiny.

Conclusion: Returning to the Source

The evidence against Abu Hurairah as a reliable narrator is overwhelming. Mathematical impossibility: 5,374 hadiths in 3-4 years, 38 times more than Abu Bakr who spent 23 years with the Prophet. Historical documentation: beaten and stripped of governorship by Umar for embezzlement and excessive hadith narration. Direct accusations: called a liar by Ali, corrected multiple times by Aisha, questioned by senior companions who knew the Prophet far better. Political corruption: sudden wealth and influence under the Umayyad dynasty that needed his narrations for political legitimacy. Problematic chains: weak narrators like Ibn Lahi’ah with burned books and failing memory. Absurd content: narrations that contradict the Quran, reason, and scientific reality.

Each piece of evidence alone raises serious questions. Together, they form an irrefutable case: Abu Hurairah cannot be trusted as a reliable source of religious guidance. Yet his narrations form a cornerstone of traditional Sunni Islam, influencing law, theology, and social practice to this day.

The Quran offers us a way out of this crisis. It declares itself complete, fully detailed, and sufficient. It identifies itself as the best hadith and questions why we would believe in other hadiths. It commands us to verify information and use our reason. When we return to the Quran as our sole source of religious law and guidance, the Abu Hurairah problem disappears—not because we’ve solved it, but because we’ve recognized that we never needed his narrations in the first place.

God’s revelation is perfect and complete. Our job isn’t to supplement it with questionable oral traditions. Our job is to read it, understand it, and live by it. When we do that—when we let the Quran be our only source of religious law—we discover a faith based on reason, justice, compassion, and direct relationship with our Creator. We discover submission to God alone, not submission to the hadith industry that has grown up around narrators like Abu Hurairah.

The numbers don’t lie. The historical record doesn’t lie. The Quran doesn’t lie. It’s time we accepted the truth and built our faith on certainty rather than conjecture.

Leave a comment