Introduction: The Weight of Words Across Millennia

When we examine religious doctrines that have shaped the beliefs of billions, we bear a solemn responsibility to investigate their textual foundations with precision and intellectual honesty. The Trinity doctrine—the belief that God exists as three co-equal, co-eternal “persons” sharing one divine essence—stands as one of the most consequential theological claims in human history. Yet remarkably few who affirm this doctrine have examined whether the original Greek texts of the New Testament actually support it, or whether the terminology used to define it even existed when those texts were written.

This examination approaches the Trinity doctrine not with hostility, but with the scholarly rigor it deserves. We will analyze the actual Koine Greek words in their first-century context, trace the historical development of trinitarian terminology through ecumenical councils, and demonstrate how certain key passages have been reinterpreted over centuries to support conclusions their original language does not sustain. The evidence reveals a consistent pattern: words that originally meant one thing in Koine Greek were gradually assigned new theological meanings centuries later, and these later meanings were then read backward into the original texts.

For those committed to truth, this investigation matters profoundly. If a doctrine claiming to represent the nature of God Himself is built upon linguistic foundations that cannot bear the weight, then intellectual and spiritual integrity demands we acknowledge this. The Quran provides a clear standard for evaluating such claims, reminding us that truth about God must be grounded in evidence, not inherited tradition.

[4:171] “O people of the scripture, do not transgress the limits of your religion, and do not say about God except the truth. The Messiah, Jesus, the son of Mary, was a messenger of God, and His word that He had sent to Mary, and a revelation from Him. Therefore, you shall believe in God and His messengers. You shall not say, ‘Trinity.’ You shall refrain from this for your own good. God is only one God. Be He glorified; He is much too glorious to have a son. To Him belongs everything in the heavens and everything on earth. God suffices as Lord and Master.”

Part 1: The Absent Word—Trinity Never Appears in Scripture

Searching for Trias in the Greek New Testament

The most fundamental observation about the Trinity doctrine is also the most frequently overlooked: the word “Trinity” does not appear anywhere in the Greek New Testament. The Greek term Τριάς (Trias), from which “Trinity” derives, is completely absent from every manuscript of every New Testament book. This is not a matter of interpretation or translation—it is a simple textual fact that can be verified by examining any Greek concordance or interlinear text. The doctrine’s foundational term is simply not present in the scripture it claims to explain.

This absence becomes even more significant when we consider the nature of the New Testament writings. The apostles and early Christian writers were addressing communities with questions about the identity of Jesus, the nature of God, and the role of the Holy Spirit. If the Trinity were a central teaching that believers needed to understand and affirm, we would expect to find explicit explanations of this three-in-one concept. Instead, we find descriptions of Jesus as God’s messenger, references to the Spirit as God’s power or breath, and consistent affirmations that God is one—but never the formulation that three distinct “persons” share one divine “essence” or “substance.”

The First Historical Appearance of Trias

The word Τριάς (Trias) first appears in Christian literature approximately 150 years after the New Testament was completed. Theophilus of Antioch, writing around 180 CE in his work “Ad Autolycum” (To Autolycus), Book II, Chapter 15, used the term in a passage about creation. His exact words are instructive: “the three days which were before the luminaries, are types of the Trinity (τριάδος), of God, and His Word, and His wisdom.” Notice carefully what Theophilus actually said: he spoke of “God, His Word, and His wisdom”—not “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” as co-equal divine persons.

This first usage reveals how far the original concept was from what the Trinity doctrine later became. Theophilus used “Trias” to describe God and two of His attributes (Word and Wisdom), not three distinct divine persons of equal status. The Latin term “Trinitas” was subsequently developed by Tertullian around 200 CE, but even Tertullian’s formulation differed significantly from the creeds that would emerge at Nicaea and Constantinople over a century later. The doctrine we now call “the Trinity” was not a first-century teaching preserved by the apostles, but a theological construction that evolved over several centuries through councils, controversies, and political pressures.

Part 2: Hebrews 1:3—The Stamp and Its Source

Examining the Greek Text

Hebrews 1:3 has long been cited by trinitarians as evidence for Christ’s divine co-equality with the Father. The verse describes Jesus in exalted terms, leading many to assume it teaches the Trinity. However, careful examination of the actual Koine Greek reveals that this verse teaches something quite different—and in fact undermines the very doctrine it is claimed to support. The Greek text reads: ὃς ὢν ἀπαύγασμα τῆς δόξης καὶ χαρακτὴρ τῆς ὑποστάσεως αὐτοῦ (“who being the radiance of His glory and the exact imprint of His substance”).

Two Greek words in this verse require careful analysis: χαρακτήρ (charaktēr) and ὑπόστασις (hypostasis). Understanding what these words meant to first-century Greek speakers—rather than what later theologians claimed they meant—is essential for grasping the verse’s actual teaching. The evidence demonstrates that both words, in their original Koine Greek context, describe a relationship of derivation and distinction, not one of co-equality and identity.

Charaktēr: The Stamp Implies an Original

The word χαρακτήρ (charaktēr) derives from the verb χαράσσω (charassō), meaning “to engrave” or “to cut into.” In first-century usage, charaktēr referred to the impression or stamp made by a die or seal—the image produced when a signet ring is pressed into wax, or when a die strikes a coin. This etymology is crucial: a stamp or imprint is, by definition, derived from an original. The seal produces the impression; the die creates the coin. There is an inherent relationship of source and derivation, original and copy.

When Hebrews describes Jesus as the χαρακτήρ of God’s ὑπόστασις, it is using the language of reproduction and representation. Just as a stamped image bears the likeness of its source while remaining distinct from it, so Jesus bears the imprint of God’s nature while remaining distinct from God. The metaphor actually argues against co-equality: a coin is not identical to the die that produced it, nor is a wax impression the same as the signet ring. The relationship described is one of derivation—the image comes from and represents the original, but is not the original itself.

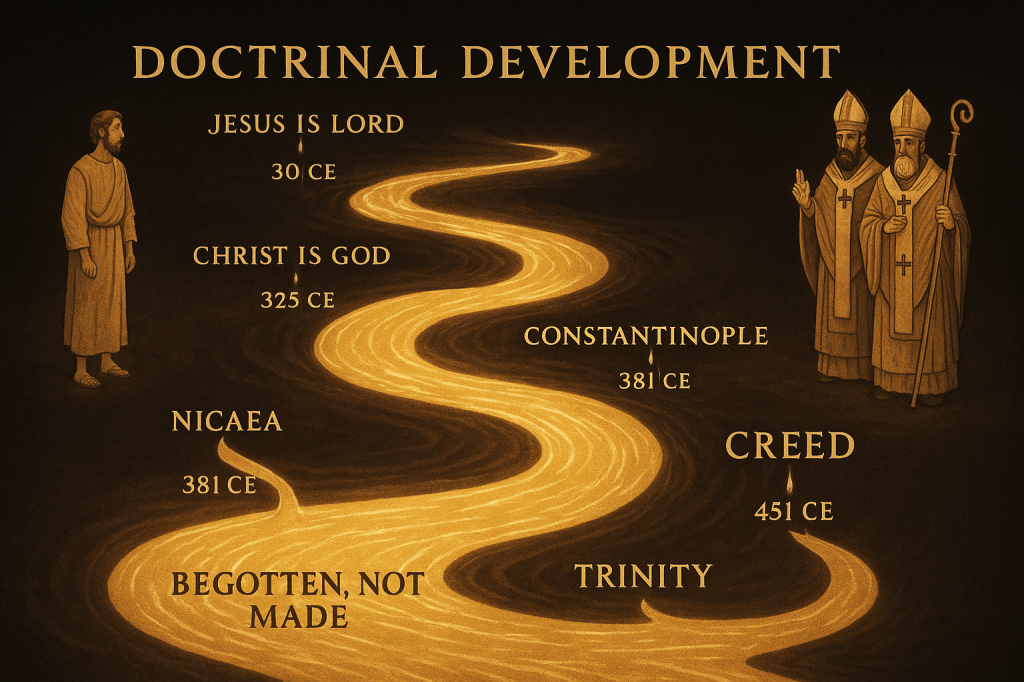

Hypostasis: Substance, Not Person

The second key term, ὑπόστασις (hypostasis), presents an even more striking case of semantic evolution. In Koine Greek of the first century, hypostasis meant “substance,” “foundation,” “underlying reality,” or “that which stands under” (from ὑπό, “under,” and στάσις, “standing”). It described the essential nature or fundamental reality of something—what a thing truly is beneath its appearances. This is precisely how the word is used in Hebrews 1:3: Jesus is the imprint of God’s underlying substance or essential nature.

The claim that hypostasis means “person”—as in “three persons (hypostases) in one essence”—is a theological development that occurred centuries after the New Testament was written. At the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, the terms hypostasis and οὐσία (ousia, “essence/substance”) were still used as synonyms. The council fathers who condemned Arius used both words interchangeably to describe God’s nature. It was not until the Council of Constantinople in 381 CE, and more definitively at Chalcedon in 451 CE, that the technical distinction between ousia (one divine essence) and hypostasis (three divine persons) became standard.

Timeline of Hypostasis Semantic Development

| Period | Meaning of Hypostasis | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Century CE (Koine Greek) | Substance, foundation, underlying reality | New Testament usage, contemporary literature |

| 325 CE (Council of Nicaea) | Used as synonym for ousia (essence) | Nicene Creed condemned those who said Son was of different “hypostasis or ousia” |

| 381 CE (Council of Constantinople) | Beginning of distinction from ousia | Cappadocian Fathers’ theological formulation |

| 451 CE (Council of Chalcedon) | Technical term for “person” in Trinity | Chalcedonian Definition: “one ousia, three hypostases” |

This historical development reveals a critical problem: trinitarians read the later technical meaning of hypostasis (person) back into Hebrews 1:3, even though that meaning did not exist when Hebrews was written. When the author of Hebrews described Jesus as the charaktēr of God’s hypostasis, the word meant God’s substance or essential nature—not God’s “person” in a trinitarian sense. The verse actually says Jesus is the imprint (derived image) of God’s substance (essential nature)—a statement of derivation and representation, not co-equal personhood within a Trinity.

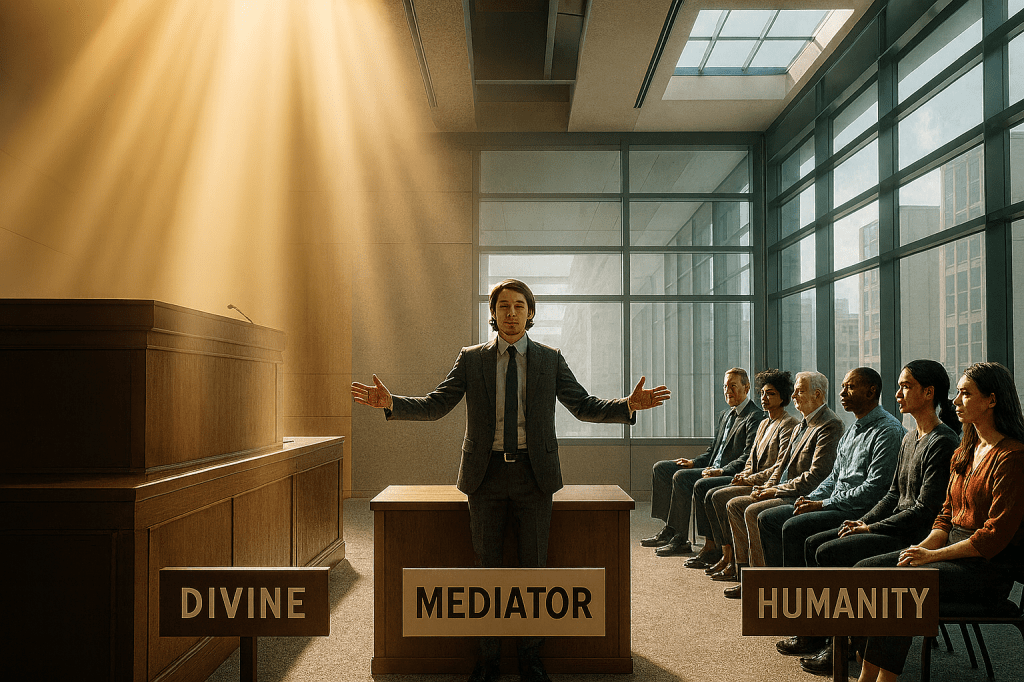

Part 3: 1 Timothy 2:5—The Mediator Cannot Be One of the Parties

The Greek Text and Its Implications

The Apostle Paul’s first letter to Timothy contains a verse that presents a fundamental logical problem for trinitarian theology. In 1 Timothy 2:5, Paul writes: εἷς γὰρ θεός, εἷς καὶ μεσίτης θεοῦ καὶ ἀνθρώπων, ἄνθρωπος Χριστὸς Ἰησοῦς—”For there is one God, and one mediator between God and mankind, the man Christ Jesus.” This verse makes two categorical statements: first, that there is one God; second, that there is one mediator between God and humanity, and this mediator is identified specifically as “a man” (ἄνθρωπος, anthrōpos).

The word ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos) in Koine Greek refers specifically to a human being, a member of the human race. It stands in contrast to θεός (theos, God) and is often used precisely to distinguish human beings from divine beings. Paul’s choice of this word is significant: he does not say Jesus is “God the Son mediating between God the Father and humanity.” He says the mediator is “a man”—using the same word (anthrōpos) that describes the humanity Jesus is mediating for. The verse presents a clear distinction: God on one side, humanity on the other, and a human mediator between them.

The Logic of Mediation

The concept of mediation carries inherent logical requirements that trinitarian theology struggles to accommodate. A mediator, by definition, must be distinct from both parties between whom mediation occurs. If a mediator were identical with one of the parties, no mediation would be possible—the party would simply be dealing with itself. When a labor dispute requires mediation, the mediator cannot be the employer or the employee; the mediator must be a third party distinct from both.

If Jesus is “God the Son,” the second person of a co-equal Trinity sharing the same divine essence with “God the Father,” then in what meaningful sense is he mediating between God and humanity? He would be God mediating between God and humanity—which is to say, God mediating between Himself and humanity. But this collapses the distinction required for mediation to function. The trinitarian might respond that Jesus mediates “in his human nature,” but Paul does not say Jesus mediates “according to his human nature”—he says the mediator is “a man.” The identification is categorical, not qualified.

The Quran affirms this understanding of Jesus’s role as a human messenger, not a divine person:

[3:59] “The example of Jesus, as far as God is concerned, is the same as that of Adam; He created him from dust, then said to him, ‘Be,’ and he was.”

This verse establishes a critical parallel: Jesus, like Adam, was created by God’s command. Neither was “begotten” in an eternal divine sense; both came into existence through God’s creative word. The mathematical confirmation noted in the Quran’s structure—Jesus and Adam are each mentioned exactly 25 times—reinforces this equivalence. If Jesus were “God the Son,” eternally co-equal with the Father, the comparison to Adam would be nonsensical. Adam was created; according to trinitarian doctrine, the Son was “eternally begotten” and never created. The Quranic parallel only makes sense if both Jesus and Adam are understood as creations of God.

Part 4: John 14:28—Greater Means Greater

Jesus’s Own Words

In the Gospel of John, Jesus makes a statement that directly addresses his relationship to the Father. The Greek text of John 14:28 records Jesus saying: ὁ πατὴρ μείζων μού ἐστιν—”The Father is greater than I.” The word μείζων (meizōn) is the comparative form of μέγας (megas, “great”), meaning “greater.” Jesus explicitly states that the Father exceeds him—the Father is greater than Jesus is.

This statement presents a significant problem for the doctrine of trinitarian co-equality. If the Father and the Son are co-equal divine persons sharing the same divine essence, in what sense can one be “greater” than the other? The standard trinitarian response is to argue that Jesus spoke these words “according to his human nature”—that is, Jesus was greater as God but lesser as a human, and in John 14:28 he was speaking from his human perspective. But this interpretation requires reading a distinction into the text that Jesus himself does not make.

The Problem of Eisegesis

Jesus does not say, “The Father is greater than my human nature.” He does not say, “According to my earthly state, the Father is greater than I.” He says simply and directly: “The Father is greater than I (μού).” The pronoun μού (mou, “me/I”) refers to Jesus himself—his person, his identity, his being. To insert qualifications that Jesus did not make—to claim he “really meant” something more nuanced than his words state—is eisegesis, the practice of reading meaning into a text rather than drawing meaning out of it.

The trinitarian interpretation requires us to believe that when Jesus said “the Father is greater than I,” his audience would have understood this to mean “the Father is greater than my human nature but co-equal with my divine nature.” Yet nothing in the context suggests such a complex dual-nature framework. The disciples to whom Jesus spoke these words showed no indication of understanding Jesus as one person with two natures in hypostatic union. That sophisticated theological formulation would not be developed until the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE—over four centuries after Jesus spoke these words.

If we take Jesus’s words at face value, without imposing later theological frameworks, the meaning is straightforward: the Father is greater than Jesus. This is consistent with Jesus’s role as God’s messenger, sent by the Father and subordinate to Him—exactly what the Quran teaches:

[5:116] “God will say, ‘O Jesus, son of Mary, did you say to the people, Make me and my mother idols beside God?’ He will say, ‘Be You glorified. I could not utter what was not right. Had I said it, You already would have known it. You know my thoughts, and I do not know Your thoughts. You know all the secrets.’”

In this Quranic passage, Jesus explicitly denies claiming divinity and acknowledges that God knows what Jesus does not know. This asymmetry of knowledge is incompatible with co-equal divine persons sharing the same omniscient divine essence. If Jesus and the Father share the same divine mind, how can the Father know Jesus’s thoughts while Jesus does not know the Father’s thoughts? The relationship described is one of creature to Creator, messenger to Sender—not co-equal persons within a divine Trinity.

Part 5: Homoousios—A Term Foreign to Scripture

The Council of Nicaea and Its Terminology

The term ὁμοούσιος (homoousios), meaning “of the same substance” or “consubstantial,” stands at the center of the Nicene Creed’s definition of Christ’s relationship to the Father. This word was intended to establish that the Son shared the same divine essence as the Father, against the Arian position that the Son was a created being. The creed declares that the Son is “of one substance (homoousios) with the Father.” This formulation has been the benchmark of trinitarian orthodoxy for seventeen centuries.

Yet homoousios, like Trias, does not appear anywhere in the Greek New Testament. Not once do the apostles, evangelists, or epistle writers use this term to describe Christ’s relationship to God. The word was borrowed from Greek philosophy and introduced into Christian theology at the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE—approximately 300 years after the New Testament was completed. The bishops at Nicaea were not simply restating what Scripture already said; they were creating new terminology to settle a dispute that earlier Christian generations had not resolved.

The Development of Trinitarian Vocabulary

The absence of homoousios from Scripture was actually a point of controversy at Nicaea itself. Some bishops objected to using non-scriptural terminology in a creed, arguing that the church should confine itself to biblical language. Emperor Constantine, who convened the council for political reasons (seeking religious unity in his empire), pressured the bishops to adopt the term. The final creed represented a political compromise as much as a theological consensus—a fact that should give pause to anyone who treats the Nicene formulation as divinely revealed truth.

The terminological development continued after Nicaea. The Council of Constantinople in 381 CE expanded the creed to include more detailed affirmations about the Holy Spirit. The Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE produced the sophisticated formulation of Christ as “one person in two natures”—language even further removed from anything in the New Testament. Each council introduced new philosophical terminology to address controversies that earlier formulations could not resolve. The doctrine we now call “the Trinity” is the end product of this centuries-long process, not a teaching present in Scripture from the beginning.

Key Ecumenical Councils and Terminological Development

Council of Nicaea (325 CE): Introduced homoousios; hypostasis and ousia used as synonyms

Council of Constantinople (381 CE): Expanded creed regarding Holy Spirit; began distinguishing hypostasis from ousia

Council of Chalcedon (451 CE): Formulated “one person, two natures” Christology; standardized “three hypostases, one ousia”

Part 6: The Logical Problems of Trinitarian Soteriology

Penal Substitutionary Atonement: A Medieval Innovation

Beyond linguistic analysis, the Trinity doctrine creates internal logical problems when combined with other doctrines built upon it—particularly theories of atonement. The dominant Protestant understanding of salvation, called “penal substitutionary atonement,” holds that Jesus bore the punishment that sinful humans deserved, satisfying God’s justice so that believers could be forgiven. This theory, however, did not exist in the early church. It was developed by Anselm of Canterbury in the 11th century (in his satisfaction theory) and refined by Calvin and Luther during the 16th-century Reformation.

When this later atonement theory is combined with trinitarian theology, logical tensions emerge. If Jesus is “God the Son,” co-equal and co-eternal with “God the Father,” then the atonement scenario involves God punishing God to satisfy God so that God can forgive humanity. The Father pours out wrath on the Son—but if they share the same divine essence and will, in what sense is this substitution rather than self-infliction? The divine essence is supposedly one; the wrath that punishes and the nature that receives punishment are the same essence. The transaction seems to occur entirely within God.

Who Forgives Whom?

Furthermore, if Jesus is fully God and the payment he makes is infinite (due to his divine nature), then the currency of payment belongs to the same party as the debt is owed. To use a human analogy: if you owe me money and I pay myself from my own account to cancel your debt, have you really been forgiven, or have I simply performed an accounting operation within my own finances? When God pays God with God’s infinite merit to satisfy God’s justice, the transaction lacks the relational reality that forgiveness requires.

These problems do not arise if Jesus is understood as God’s human messenger—a man chosen by God, empowered by God, and approved by God to deliver God’s message to humanity. In this understanding, Jesus does not “pay” for sins through his suffering; rather, he delivers God’s guidance that enables people to repent and receive God’s mercy. Forgiveness comes from God alone, not from a transaction within a multi-personal divine being.

[19:35] “It does not befit God that He begets a son, be He glorified. To have anything done, He simply says to it, ‘Be,’ and it is.”

This verse cuts through the complexity of trinitarian speculation with simple clarity. God does not need to beget; He commands. God does not need to arrange transactions with Himself; He forgives whom He wills. The elaborate theological machinery of Trinity and substitutionary atonement, developed over centuries of philosophical speculation, is unnecessary when we recognize God as He presents Himself: one God, without partners, requiring no mediation by other divine persons because He is fully capable of relating to His creation directly.

Part 7: Setting Up Lords Besides God

The Quranic Warning

The Quran addresses the Christian tendency toward deifying Jesus and religious leaders with remarkable directness. The pattern it identifies—taking religious figures as “lords” alongside God—describes precisely what happened in the development of trinitarian doctrine. Church councils, composed of bishops and scholars, determined what Christians must believe about God’s nature. Their philosophical formulations, using non-scriptural terminology, became binding orthodoxy enforced by imperial power and ecclesiastical authority.

[9:31] “They have set up their religious leaders and scholars as lords, instead of God. Others deified the Messiah, son of Mary. They were all commanded to worship only one God. There is no God except He. Be He glorified, high above having any partners.”

This verse identifies two forms of associating partners with God: following religious leaders’ teachings instead of God’s, and deifying the Messiah. Both forms characterize trinitarian Christianity. The Trinity doctrine itself represents the deification of Jesus—elevating a human messenger to co-equal divine status with God. And the process by which this doctrine developed represents the elevation of religious authority—councils, creeds, and traditions—above the clear teachings of Scripture.

When Human Authority Defines Divine Nature

Consider the implications: the nature of God Himself—the most fundamental question in any religious framework—was determined by majority vote at church councils convened by Roman emperors. Bishops debated, argued, and eventually voted on whether the Son was “of the same substance” or “of similar substance” as the Father. Emperors exiled bishops who dissented from the majority position. Political and ecclesiastical power, not scriptural clarity, established what became orthodoxy.

This is precisely what the Quran warns against. When religious scholars define God’s nature using categories He never revealed, and when following these scholarly definitions becomes required for salvation, those scholars have been set up as lords alongside God. Their authority to define God’s nature places them in a God-like position—determining truth about the divine that God Himself did not clearly reveal in His word.

Part 8: The Clarity of Pure Monotheism

Surah Al-Ikhlas: The Essence of Divine Unity

Against the complexity of trinitarian theology—with its technical vocabulary, philosophical distinctions, and centuries of conciliar development—the Quran presents a vision of God characterized by elegant simplicity and absolute clarity. Surah 112, Al-Ikhlas (The Sincerity), contains just four verses, yet these verses constitute what Islamic tradition considers equal to one-third of the Quran in significance. They present God’s nature without philosophical elaboration, without non-revealed terminology, without the need for councils to interpret:

[112:1] “Proclaim, ‘He is the One and only God.”

[112:2] “The Absolute God.”

[112:3] “Never did He beget. Nor was He begotten.”

[112:4] “None equals Him.’”

Each verse addresses a specific error in human conceptions of divinity. “He is the One and only God” negates polytheism in all forms—including the subtle polytheism of multiple divine persons. “The Absolute God” (Al-Samad) describes God as completely self-sufficient, needing nothing outside Himself—not even other divine “persons” to constitute His being. “Never did He beget, nor was He begotten” directly refutes the trinitarian claim that the Son was “eternally begotten” of the Father. “None equals Him” eliminates any possibility of co-equal divine persons sharing God’s unique status.

The Incomparability of God

The Quran emphasizes repeatedly that nothing can be compared to God, that nothing equals Him, that nothing resembles Him. This absolute uniqueness is incompatible with the trinitarian claim that three distinct persons share one divine nature. If the Son and Spirit “share” God’s nature with the Father, then in some sense they equal the Father—they possess the same essence, the same attributes, the same glory. But the Quran declares: “None equals Him.”

[42:11] “Initiator of the heavens and the earth. He created for you from among yourselves spouses—and also for the animals. He thus provides you with the means to multiply. There is nothing that equals Him. He is the Hearer, the Seer.”

The phrase “there is nothing that equals Him” (لَيْسَ كَمِثْلِهِۦ شَىْءٌ) uses emphatic language to establish God’s absolute uniqueness. The Arabic construction emphasizes totality: not a single thing in existence equals God or resembles Him. This statement is not merely about idols or false gods—it encompasses everything that exists. If the Son and Spirit exist as divine persons, they would be “things” that equal God in divinity. Yet the Quran declares nothing equals Him—no exceptions, no qualifications, no trinitarian distinctions permitted.

Part 9: The Historical Pattern of Doctrinal Development

From Simple Confession to Complex Creed

The earliest Christian confession was remarkably simple: “Jesus is Lord” or “Jesus is the Messiah.” These affirmations acknowledged Jesus’s authority and messianic status without requiring detailed metaphysical claims about his nature or relationship to God. The New Testament presents diverse ways of speaking about Jesus—son of God, son of man, logos, image of God, firstborn of creation—without harmonizing these into a systematic doctrine. The diversity itself suggests that the earliest Christians had not yet developed (or received from the apostles) a unified doctrine of Christ’s divine nature.

The progression from these simple confessions to the elaborate formulations of Nicaea, Constantinople, and Chalcedon reveals a pattern: complexity developed over time. Each council introduced new terminology because previous formulations proved inadequate to resolve ongoing disputes. If the apostles had taught a clear trinitarian doctrine, such development would be unnecessary—the church would simply repeat what it received. Instead, we see continuous theological innovation, each generation building on (and often contradicting) the previous generation’s formulations.

The Pressure of External Philosophy

Much of the vocabulary and conceptual framework of trinitarian doctrine came not from Scripture but from Greek philosophy. Terms like “essence” (ousia), “substance” (hypostasis in its later technical sense), “person” (prosopon/persona), and “nature” (physis) were borrowed from philosophical discourse and applied to theological questions. Platonic and Neoplatonic concepts of emanation influenced how the relationship between Father and Son was conceptualized. Aristotelian categories of substance and accident shaped discussions of how three persons could share one essence.

This philosophical influence was not neutral. Greek philosophy carried assumptions about the nature of divinity that differed significantly from biblical monotheism. The Platonic idea of divine “emanation”—lower realities flowing from higher ones—provided a conceptual model for the Son “proceeding” from the Father. But this model, however philosophically sophisticated, is not found in the Hebrew prophets or the words of Jesus himself. It represents the synthesis of biblical religion with Greek metaphysics—a synthesis that produced something neither fully biblical nor fully Greek, but distinctively new.

Part 10: Responding to Common Trinitarian Arguments

“The Word Was God” (John 1:1)

Trinitarians frequently cite John 1:1—”In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God”—as proof of Christ’s deity. However, the Greek text presents complexities that English translations obscure. The phrase θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος (theos ēn ho logos) lacks the definite article before theos. Greek grammar typically uses the article to indicate a specific identity; its absence often indicates qualitative meaning—describing what something is like rather than identifying it with a specific being.

Thus, the phrase could be translated “the Word was divine” or “the Word was god-like” rather than “the Word was God” (identifying the Word with the being previously called “God”). This reading is consistent with the rest of John’s prologue, which describes the Word as being “with God” (indicating distinction) and as being the agent through whom God created (indicating subordination). The Word is divine in nature but distinct from the God who speaks the Word. This aligns with the Quranic description of Jesus as God’s “word” sent to Mary—a divine communication, not a co-equal divine person.

“I and the Father Are One” (John 10:30)

Another frequently cited proof-text is John 10:30, where Jesus says, “I and the Father are one.” Trinitarians take this as a claim to ontological unity with the Father—sharing the same divine being. However, the Greek word for “one” here is ἕν (hen), which is neuter, not masculine. If Jesus were claiming to be the same person or being as the Father, we would expect the masculine εἷς (heis). The neuter form suggests unity of purpose, will, or function rather than identity of being.

This interpretation is confirmed by John 17:21-22, where Jesus prays that his disciples “may be one as we are one.” Clearly, Jesus is not praying that his disciples become a single being or share one divine essence. He is praying for unity of purpose, love, and mission. If “one” means ontological unity when applied to Jesus and the Father, it would have to mean the same when applied to the disciples—a conclusion no trinitarian accepts. Consistency requires reading both usages the same way: unity of purpose and will, not identity of being.

“Before Abraham Was, I Am” (John 8:58)

The statement “Before Abraham was, I am” (πρὶν Ἀβραὰμ γενέσθαι ἐγὼ εἰμί) is taken by trinitarians as Jesus claiming the divine name revealed to Moses at the burning bush. However, the phrase ἐγὼ εἰμί (egō eimi) simply means “I am” and is used dozens of times in the New Testament in ordinary contexts. The Septuagint (Greek Old Testament) renders God’s self-identification in Exodus 3:14 differently: ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ὤν (egō eimi ho ōn), “I am the Being” or “I am He who is.”

Jesus’s statement in John 8:58 can be understood as a claim to pre-existence—his existence before Abraham in God’s plan and purpose—without being a claim to be the God of Exodus. The prophets were known to God before their birth (Jeremiah 1:5); the Messiah was promised before Abraham lived. Jesus’s pre-existence in God’s foreknowledge and purpose is consistent with his role as the promised Messiah without requiring ontological co-equality with the Father.

Part 11: The Witness of Jesus Himself

What Jesus Called Himself

Throughout the Gospels, Jesus’s most common self-designation is “Son of Man”—a title emphasizing his humanity and connecting him to the prophetic figure in Daniel 7. He does not call himself “God the Son” or “the Second Person of the Trinity.” When addressed as “Good Teacher,” Jesus responds, “Why do you call me good? No one is good except God alone” (Mark 10:18)—a strange response if Jesus understood himself to be God. When asked about the greatest commandment, Jesus affirms the Shema: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one” (Mark 12:29)—the foundational confession of Jewish monotheism, with no trinitarian qualification.

Jesus consistently distinguished himself from the Father. He prayed to the Father—but if he shared the same divine essence and will, prayer to himself would be meaningless. He said he could do nothing by himself but only what he saw the Father doing—but if he were co-equal God, he would not be dependent on seeing the Father’s actions. He said he came not to do his own will but the will of the Father who sent him—but a co-equal divine person does not get “sent” by another co-equal divine person. The language of mission, dependence, and obedience pervades Jesus’s self-description, all of which is consistent with being God’s messenger but inconsistent with being God’s co-equal.

What Jesus Taught About God

Jesus taught his followers to pray to “Our Father in heaven”—not to himself, not to a Trinity, but to the Father. He taught that eternal life consists in knowing “you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent” (John 17:3). Notice the distinction: the Father is identified as “the only true God,” while Jesus is identified as one whom God “sent.” If Jesus were equally “the only true God,” the description would be incomplete and misleading. The verse makes perfect sense if Jesus is God’s messenger; it creates theological tension if Jesus is God’s co-equal.

The Quran affirms this understanding of Jesus’s teaching:

[5:117] “‘I told them only what You commanded me to say, that: You shall worship God, my Lord and your Lord.’ I was a witness among them for as long as I lived with them. When You terminated my life on earth, You became the Watcher over them. You witness all things.”

According to this passage, Jesus taught what God commanded him to teach: worship God, who is “my Lord and your Lord.” Jesus identifies God as his Lord—not as his co-equal within a Trinity, but as his Lord whom he serves and obeys. This is consistent with Jesus’s role as God’s messenger and completely inconsistent with the trinitarian claim that Jesus is himself Lord in the same divine sense as the Father.

Part 12: The Testimony of the Disciples

Peter’s Confession

When Jesus asked his disciples who they believed him to be, Peter responded: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:16). Jesus praised this confession, calling it revelation from the Father. Yet notice what Peter confessed: “the Messiah” (Christ) and “Son of the living God”—not “God the Son” or “the Second Person of the Trinity.” The title “Messiah” identifies Jesus as the promised anointed one, a human figure empowered by God for a special mission. “Son of God” in Jewish context denoted a special relationship with God—kings, angels, and the righteous were called “sons of God”—not ontological divinity or co-equal personhood within God’s being.

If trinitarian doctrine were apostolic teaching, we would expect Peter’s confession to reflect it. Peter had the opportunity to declare, “You are God” or “You are divine” or “You are equal to the Father.” Instead, he used categories consistent with Jewish messianic expectation: Messiah and Son of God. These titles identify Jesus’s role and relationship, not his participation in a divine Trinity.

The Early Preaching

The book of Acts records the earliest Christian preaching. Peter’s sermon at Pentecost (Acts 2) identifies Jesus as “a man attested to you by God with mighty works and wonders and signs that God did through him” (Acts 2:22). Note the agency: God did works through Jesus; Jesus was God’s instrument. Peter continues: “God has made him both Lord and Christ, this Jesus whom you crucified” (Acts 2:36). Jesus was “made” Lord and Christ—language suggesting appointment or conferral, not eternal co-equality.

Throughout Acts, the apostolic preaching presents Jesus as God’s servant, God’s appointed one, the prophet Moses foretold. The pattern is consistent: God is the primary actor; Jesus is God’s agent. God raised Jesus; God exalted Jesus; God will judge through Jesus. This is the language of agency and appointment, perfectly consistent with Jesus as God’s messenger but requiring significant reinterpretation to fit trinitarian categories.

Part 13: The Question of Worship

Did the Early Christians Worship Jesus as God?

Trinitarians point to instances where Jesus received proskunesis (bowing, homage) as evidence that early Christians worshipped him as God. However, the Greek word προσκυνέω (proskuneō) covers a range of meanings from simple respect to full divine worship. In Matthew 18:26, a servant “worships” (proskuneō) his king; in Revelation 3:9, people will “worship” at the feet of the Philadelphia church. The word alone does not prove divine worship.

More significantly, the New Testament consistently depicts prayer and worship directed to God the Father, with Jesus as mediator or model. The Lord’s Prayer addresses “Our Father in heaven.” Paul’s letters typically give glory and thanks to “God the Father” or “the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Revelation depicts worship in heaven directed to “the One who sits on the throne”—with Jesus (the Lamb) receiving honor alongside but distinct from God. The pattern suggests reverence for Jesus within the context of worship directed to God, not worship of Jesus as God.

[5:73] “Pagans indeed are those who say that God is a third in a trinity. There is no God except the one God. Unless they refrain from saying this, those who disbelieve among them will incur a painful retribution.”

The Quran’s condemnation is unambiguous. Those who make God “a third in a trinity” have committed an act of paganism—associating partners with the one true God. The warning is serious: unless they refrain, painful retribution awaits. This is not a marginal issue or a secondary dispute; the nature of God and the sin of shirk (associating partners with Him) represent the most fundamental questions in divine revelation.

Conclusion: The Weight of Evidence

Summarizing the Linguistic Evidence

Our examination has revealed a consistent pattern. The word “Trinity” (Trias) does not appear in the Greek New Testament and was first used by Theophilus of Antioch around 180 CE in a context that did not describe three co-equal divine persons. The word hypostasis in Hebrews 1:3 meant “substance” or “reality,” not “person”—the technical trinitarian meaning developed 400+ years later. The word charaktēr (stamp/imprint) implies derivation from an original, not co-equality with it. The word anthrōpos in 1 Timothy 2:5 specifically identifies Jesus as “a man,” distinct from the God between whom and humanity he mediates. The term homoousios, central to the Nicene Creed’s trinitarian definition, does not appear anywhere in Scripture and was introduced 300 years after the New Testament was completed.

The linguistic evidence does not support the Trinity doctrine. The terminology used to define the doctrine was either absent from Scripture or used with different meanings than trinitarians claim. The doctrine required centuries of philosophical development, church councils, and imperial enforcement to reach its classical formulation. Whatever the Trinity is, it is not a teaching clearly present in the first-century texts that trinitarians claim as their authority.

The Alternative: Simple, Pure Monotheism

Against this complex historical development stands the simple clarity of Quranic monotheism. God is one—not three-in-one, not one essence in three persons, not a unity requiring philosophical explanation. God does not beget; He has no “only-begotten Son” in an ontological sense. Nothing equals Him; no divine persons share His unique status. Jesus was a messenger, honored and blessed, but human—created by God’s word just as Adam was created.

This is not a rejection of Jesus’s importance or honor. It is a restoration of his actual role: the Messiah, a prophet, a messenger of God. It preserves the proper distinction between Creator and creation, between the one who sends and the one who is sent, between the Lord and His servant. It requires no councils to define, no philosophical terminology to explain, no imperial power to enforce. It is the natural reading of what Jesus himself taught: “The Lord our God, the Lord is one.”

[112:1-4] “Proclaim, ‘He is the One and only God. The Absolute God. Never did He beget. Nor was He begotten. None equals Him.’”

The truth about God was never complicated. Human theological innovation complicated it. The return to pure monotheism—worshipping the One God alone, without partners, without philosophical elaboration—is both a return to the original teaching of all God’s messengers and an embrace of the final revelation that corrects the corruptions introduced over centuries of human speculation. May we have the courage to examine our inherited beliefs, the humility to follow evidence where it leads, and the sincerity to worship God alone as He truly is.

Bibliography and Further Reading:

For Greek textual analysis: Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece (28th Edition); Liddell-Scott-Jones Greek-English Lexicon

For historical council documents: Denzinger, Enchiridion Symbolorum; Kelly, J.N.D., Early Christian Doctrines

For Quranic references: Final Testament (Authorized English Translation by Rashad Khalifa)

Leave a comment