Introduction: Examining the Claims

Among the most persistent claims in religious discourse is the assertion that the Torah represents an eternal, unchangeable covenant that cannot be superseded by any subsequent revelation. Proponents of this view argue that God’s covenant with Israel at Sinai was established “forever,” that the Torah contains no internal contradictions, and that no future scripture could hold authority over the teachings given to Moses. These claims form the foundation upon which Jewish theology rejects the authority of both the Christian New Testament and the Quran. Yet when we examine these claims against the evidence found within the Hebrew Bible itself, combined with the historical record and the Quran’s own testimony, a very different picture emerges.

This examination is not undertaken with hostility toward Jewish tradition or its adherents. Rather, it proceeds from a sincere desire to understand what God has actually revealed and to follow divine guidance wherever it leads. The Quran itself affirms that the Torah contained “guidance and light” and that sincere Jews who believe in God and the Last Day and lead righteous lives will receive their recompense from their Lord. The question before us is not whether God spoke through the prophets of Israel – He certainly did – but whether the Torah as we have it today represents the complete, uncorrupted, and final word of God to humanity. The evidence, as we shall see, answers decisively in the negative.

Part 1: The Meaning of “Forever” – What Olam Actually Signifies

Hebrew Terminology and Its Limitations

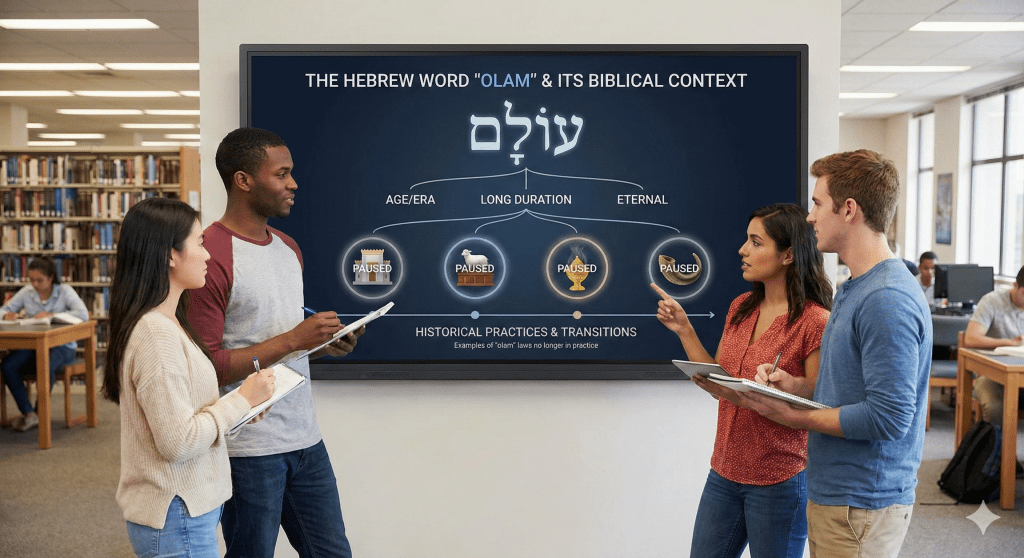

The foundation of the “eternal Torah” argument rests primarily on the Hebrew word “olam” (עוֹלָם), which appears in numerous passages describing laws and institutions as lasting “forever.” English translations render this word as “eternal,” “everlasting,” or “forever,” leading readers to conclude that these commandments can never be altered or superseded. However, a careful study of Hebrew lexicography reveals that olam does not necessarily denote absolute, infinite eternity in the philosophical sense. Rather, olam fundamentally means “age,” “duration,” “long time,” or “as long as conditions permit.” The word derives from a root meaning “hidden” or “concealed,” referring to time whose end is not immediately visible – not time that has no end.

This distinction is crucial because the same word is used for institutions and laws that observant Jews themselves acknowledge have ended. The Aaronic priesthood was established “olam” (Exodus 29:9), yet no Levitical priesthood functions today. The Passover lamb sacrifice was commanded “olam” (Exodus 12:14), yet Jews cannot perform this sacrifice without a temple. The burning of incense was to be “olam” (Exodus 30:8), the showbread was to be arranged “olam” (Leviticus 24:8), and the Year of Jubilee was to be observed “olam” (Leviticus 25:10) – yet none of these practices continue. If olam meant absolute, unchangeable eternity, how can these “eternal” laws be suspended indefinitely? The honest answer is that olam designates the duration of a covenant within its intended age, not an absolute, philosophical eternity that transcends all time.

The Sabbath as a Sign “Between Me and the Children of Israel”

Consider the Sabbath commandment, often cited as the pinnacle of eternal law. Exodus 31:16-17 states: “Therefore the children of Israel shall keep the sabbath, to observe the sabbath throughout their generations, for a perpetual covenant. It is a sign between Me and the children of Israel forever.” Notice the explicit limitation: the Sabbath is described as “a sign between Me and the children of Israel.” It is not presented as a universal law for all humanity throughout all time. The covenant at Sinai was made with a specific people who had been brought “out of Egypt” (Exodus 20:2). God’s relationship with humanity has always been broader than His specific covenant with Israel, as we shall see when examining God’s dealings with other nations and peoples.

Furthermore, even within Jewish tradition, the principle that the Torah can be modified under divine authority is well established. The rabbis developed the concept of “pikuach nefesh” (saving life), which allows the suspension of virtually any commandment – including the Sabbath – to preserve human life. If the Torah were absolutely immutable, no such principle could exist. The Talmud records extensive debates about which laws are binding and under what circumstances, demonstrating that even within traditional Judaism, the Torah is not treated as an unchangeable monolith. The question is not whether divine law can be modified, but by whose authority such modification occurs. When God Himself sends a new messenger with updated revelation, the Torah’s own principles demand acceptance.

Part 2: Contradictions in the Torah – The Nacham Problem

Does God Repent or Not?

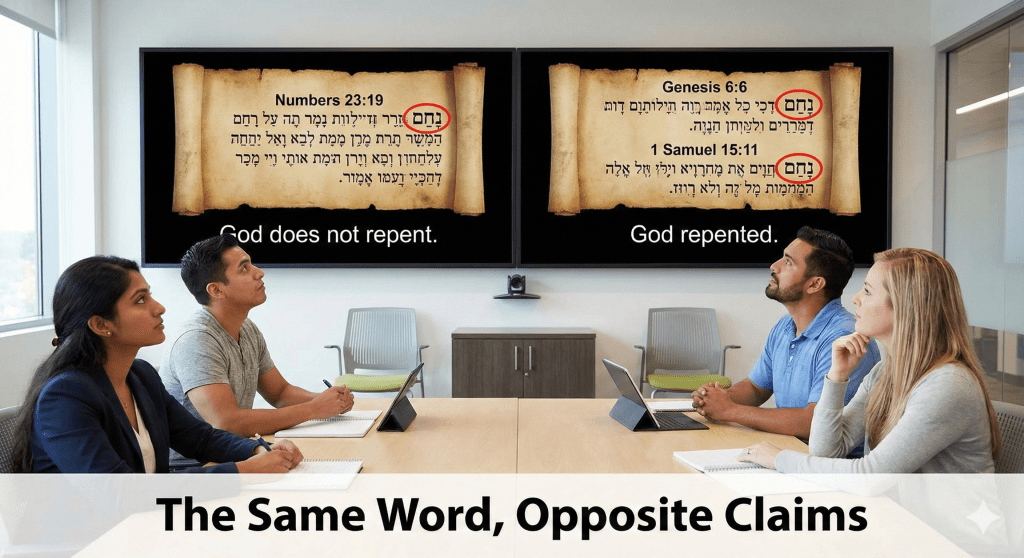

One of the most striking internal contradictions in the Torah involves the Hebrew word nacham (נָחַם), which means to repent, regret, relent, or change one’s mind. This is not a matter of translation ambiguity – the same Hebrew word in the same grammatical form (Niphal) appears in passages that directly contradict one another. Numbers 23:19 declares: “God is not a man that He should lie, nor a son of man that He should repent (nacham). Has He said, and will He not do it? Or has He spoken, and will He not make it good?” This verse emphatically denies that God experiences nacham – repentance or change of mind. It presents divine constancy as fundamentally different from human fickleness.

Yet Genesis 6:6 states: “And the LORD repented (nacham) that He had made man on the earth, and it grieved Him at His heart.” Here the same word nacham is applied directly to God’s emotional response to human wickedness before the flood. Exodus 32:14 similarly records that after Moses interceded for Israel following the golden calf incident, “the LORD repented (nacham) of the evil which He thought to do unto His people.” These verses describe God experiencing the very nacham that Numbers 23:19 claims God cannot experience. The contradiction is not resolved by appealing to different Hebrew words or translation choices – the same word is used throughout.

The 1 Samuel 15 Paradox

Perhaps most remarkably, this contradiction appears within a single chapter of Scripture. In 1 Samuel 15:11, God says to Samuel: “I regret (nacham) that I have made Saul king, for he has turned back from following Me.” God expresses divine nacham – regret over a previous decision. Yet just eighteen verses later, in 1 Samuel 15:29, Samuel declares: “And also the Glory of Israel will not lie or repent (nacham), for He is not a man that He should repent (nacham).” In the same chapter, using the same word, Scripture both affirms and denies that God experiences nacham. No hermeneutical gymnastics can resolve this direct contradiction appearing within the same narrative context.

Defenders of biblical inerrancy have proposed various solutions – that God’s “repentance” is anthropomorphic language, that different aspects of God’s nature are being described, or that the contexts differ in significant ways. Yet these explanations cannot escape the fundamental problem: Scripture uses the same word to assert and deny the same divine attribute. If the Torah were perfectly preserved and internally consistent, as some claim, such contradictions would not exist. The Quran addresses this directly, challenging humanity to find contradictions within it as proof that it comes from God – a challenge it can issue precisely because, unlike the Torah, it maintains internal consistency.

[4:82] “Why do they not study the Quran carefully? If it were from other than God, they would have found in it numerous contradictions.”

Part 3: Can Anyone See God? – Another Contradiction

Face to Face or Fatal Encounter?

The Torah presents another irreconcilable contradiction regarding whether human beings can see God. Exodus 33:20 records God’s declaration to Moses: “You cannot see My face; for no man shall see Me and live.” This verse establishes a clear principle: seeing God’s face results in death. No human can survive a direct visual encounter with the divine presence. Yet just eleven verses earlier, in Exodus 33:11, we read: “And the LORD spoke to Moses face to face, as a man speaks to his friend.” How can Moses speak with God “face to face” if no man can see God’s face and live? The expressions cannot both be literally true simultaneously.

Genesis 32:30 presents the same difficulty. After wrestling with a mysterious figure all night, Jacob declares: “I have seen God face to face, and my life is preserved.” Jacob explicitly notes that he survived despite seeing God face to face – directly contradicting the principle stated in Exodus 33:20. Some interpreters suggest that Jacob wrestled with an angel rather than God Himself, but the text has Jacob naming the place Peniel precisely because he saw “God face to face.” The narrative presents this as an encounter with God, not merely an angelic messenger. Either humans can see God and survive, or they cannot – the Torah says both.

The Implications for Textual Integrity

These contradictions matter because they demonstrate that the Torah as we have it today cannot be the perfectly preserved, inerrant word of God that some claim. Either the original revelation contained contradictions (which would impugn God’s consistency), or the text has been altered, corrupted, or compiled from different sources with different theological perspectives. Neither option supports the claim that the Torah is an eternal, unchangeable document that supersedes all subsequent revelation. The Quran acknowledges this reality, warning about those who “distort the scripture with their own hands, then say, ‘This is what God has revealed.’”

[2:79] “Therefore, woe to those who distort the scripture with their own hands, then say, ‘This is what God has revealed,’ seeking a cheap material gain. Woe to them for such distortion, and woe to them for their illicit gains.”

The Quran does not claim that the original Torah was defective – rather, it affirms that God revealed the Torah with guidance and light. The problem lies in what happened subsequently: scribal alterations, theological editing, and the compilation of contradictory sources into a single text. The historical evidence for this process is overwhelming, as we shall see when examining the textual history of the Hebrew Bible.

Part 4: Isaiah 45:7 – Does God Create Evil?

The Problem of Divine Evil-Making

Isaiah 45:7 presents one of the most theologically challenging statements in the Hebrew Bible. In the Hebrew text, God declares: “I form light and create darkness, I make peace and create evil (ra).” The Hebrew word “ra” (רָע) is unambiguous – it means evil, harm, calamity, or wickedness. This verse attributes the creation of evil directly to God. Some translations attempt to soften this by rendering ra as “calamity” or “disaster,” but the word’s semantic range clearly includes moral evil. The same word describes the fruit of the tree of knowledge of “good and evil (ra)” in Genesis, where it clearly carries moral connotations.

This attribution of evil-creation to God stands in tension with other biblical passages and creates significant theological problems. How can a perfectly good God be the source of evil? Jewish commentators have struggled with this verse for millennia, proposing that God creates the capacity for evil through free will, or that “evil” here means only natural disasters rather than moral wickedness. Yet the plain reading of the text attributes ra directly to divine creative action. Later biblical books seem to acknowledge this difficulty – the Book of James in the New Testament explicitly states that “God cannot be tempted by evil, neither does He tempt any man,” and 1 John declares that “in Him is no darkness at all.”

How the Quran Addresses Divine Attributes

The Quran presents a consistent theology regarding God and evil. God is never presented as the creator of evil in any sense. Rather, evil results from Satan’s rebellion and human choices to follow Satan’s path. The distinction is clear: God creates the capacity for choice, and creatures misuse that capacity through their own volition. This theological consistency is one of the marks of the Quran’s divine origin – it maintains coherent teaching about God’s nature throughout, never attributing to God qualities that contradict His perfect goodness. When the Quran issues its challenge to find internal contradictions, the challenge extends to theological consistency as well as factual claims.

The Torah’s attribution of evil-creation to God represents either a genuine theological teaching (which creates irreconcilable difficulties) or a corruption of the original revelation (which confirms the Quran’s account of textual distortion). In either case, the claim that the Torah is perfectly preserved and internally consistent cannot be maintained. The Quran’s superseding authority thus rests not on arbitrary replacement but on the correction of corruptions and the restoration of theological truth.

Part 5: Historical Evidence of Textual Corruption

The Dead Sea Scrolls Testimony

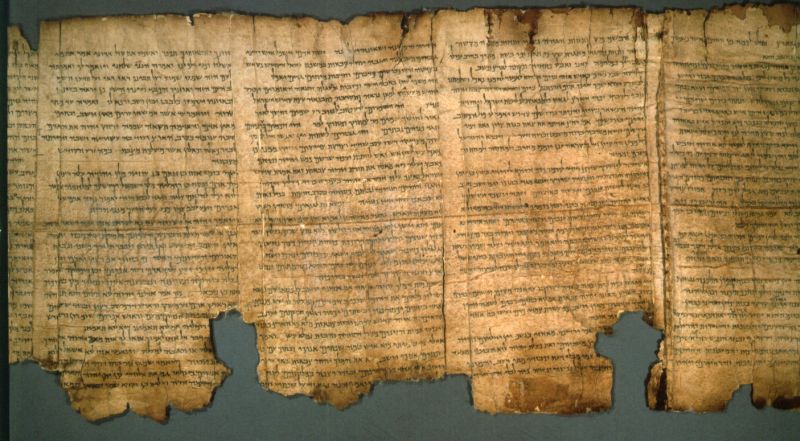

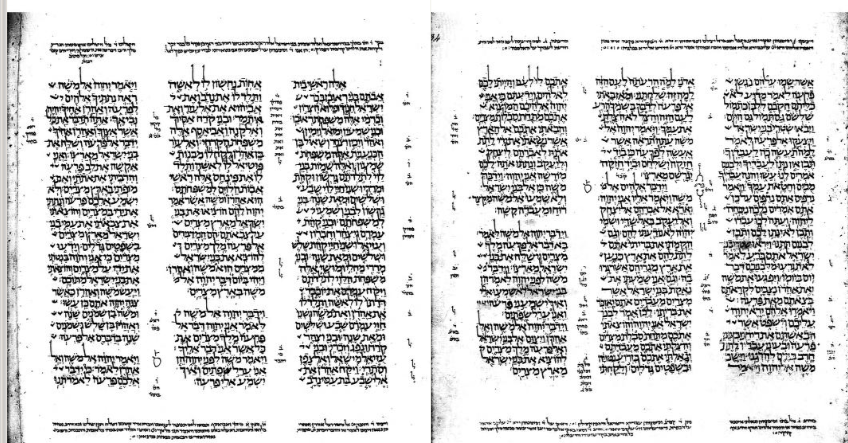

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran in 1947 provided unprecedented access to Hebrew biblical manuscripts approximately 1,000 years older than the earliest complete Masoretic texts. While some scrolls closely match the later Masoretic tradition, others reveal significant variations. The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsa-a), for example, contains over 1,400 textual variants from the Masoretic text. The scrolls also include texts of Jeremiah that are approximately 15% shorter than the Masoretic version, matching instead the Septuagint tradition. These findings demonstrate that multiple textual traditions of biblical books existed simultaneously in ancient Israel, with no single authoritative text.

1st century BCE Ink on parchment

Government of Israel HU 95.57/27

Source: The Great Isaiah Scroll can be viewed in its entirety at the Israel Museum Digital Dead Sea Scrolls Project. High-resolution manuscript images are available at the Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library.

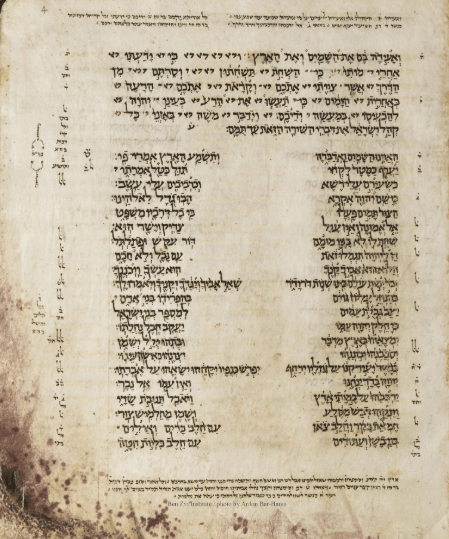

Codex Leningradensis (Oldest Complete Masoretic Text – 1008 CE)

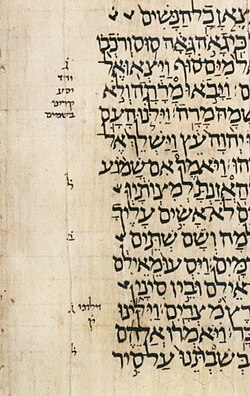

The Samaritan Pentateuch presents even more striking evidence of textual diversity. This text, preserved by the Samaritan community, contains approximately 6,000 differences from the Jewish Masoretic Torah. While many are minor spelling variations, others involve significant additions or alterations. The Samaritans claim their text preserves the original Torah more accurately than the Jewish version, while Jews make the opposite claim. The existence of these competing textual traditions, each claiming authenticity, demonstrates that no perfectly preserved original Torah exists today. Which tradition, if any, faithfully represents the original revelation? The question cannot be definitively answered from the manuscripts themselves.

Source: Samaritan Pentateuch manuscripts are held at the British Library and the Chester Beatty Library. The oldest complete Masoretic text is the Aleppo Codex (930 CE), now partially damaged, and the Codex Leningradensis (1008 CE).

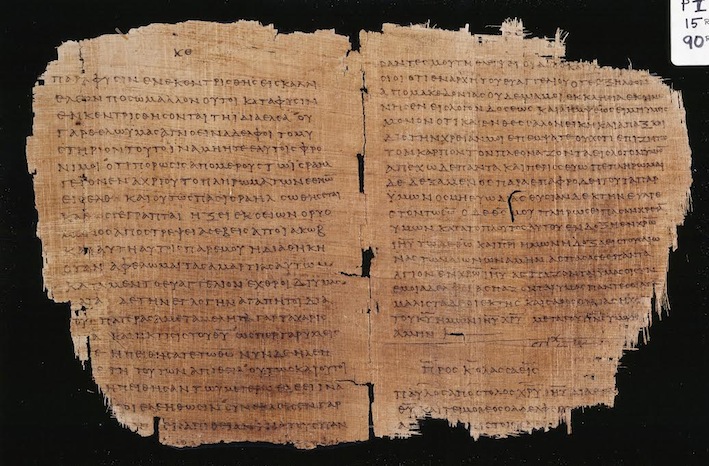

The Septuagint and Translation Evidence

The Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures made in Alexandria beginning around the 3rd century BCE, provides further evidence of textual diversity. This translation was made from Hebrew manuscripts that in many places differ from the later Masoretic text. Where the Dead Sea Scrolls can be compared with both traditions, they sometimes agree with the Septuagint against the Masoretic text, demonstrating that the Septuagint’s Hebrew source was not simply a defective manuscript but represented a legitimate alternative textual tradition. Early Christians used the Septuagint as their Scripture, and some New Testament quotations match the Septuagint where it differs from the Hebrew.

The Talmud itself acknowledges textual variations in ancient Torah scrolls. Tractate Soferim (6:4) records that three Torah scrolls were kept in the Temple, and when they disagreed with one another, the reading of two against one was adopted. This rabbinical testimony explicitly acknowledges that even Temple Torah scrolls did not perfectly agree with one another. The scribes selected readings by majority vote rather than by appeal to an original perfect manuscript – because no such manuscript existed even in Temple times. This evidence from within Jewish tradition itself undermines the claim of perfect textual preservation.

Source: The Septuagint tradition is preserved in Codex Sinaiticus (4th century CE) and Codex Vaticanus at the Vatican Library. The Talmudic reference to Temple scroll variations is found in Tractate Soferim 6:4, available in the Sefaria digital library.

[2:75] “Do you expect them to believe as you do, when some of them used to hear the word of God, then distort it, with full understanding thereof, and deliberately?”

Part 6: The Torah Prophesies Its Own Succession

Deuteronomy 18 – A Prophet Like Moses

Within the Torah itself, God announces the coming of future prophets whose words must be heeded. Deuteronomy 18:18-19 records God’s declaration to Moses: “I will raise up for them a Prophet like you from among their brethren, and will put My words in His mouth, and He shall speak to them all that I command Him. And it shall be that whoever will not hear My words, which He speaks in My name, I will require it of him.” This passage explicitly establishes that God will send future prophets whose messages carry divine authority. To reject such prophets is to disobey God Himself. The Torah thus contains within itself the principle of progressive revelation.

The phrase “a Prophet like you” carries particular significance. Moses was unique among Israelite prophets in receiving comprehensive written revelation – the Torah itself. A prophet “like Moses” would therefore also bring written revelation, a new scripture for a new age. Jewish tradition has debated the identity of this prophet, with some applying it to Joshua or the prophetic office generally. Yet the singular language (“a Prophet”) and the comparison to Moses suggest a specific figure of unique stature. The Quran identifies this as a reference to Muhammad, who – like Moses – received comprehensive written revelation, led a community from oppression to freedom, and established divine law for his people.

[7:157] “(4) follow the messenger, the gentile prophet (Muhammad), whom they find written in their Torah and Gospel. He exhorts them to be righteous, enjoins them from evil, allows for them all good food, and prohibits that which is bad, and unloads the burdens and the shackles imposed upon them. Those who believe in him, respect him, support him, and follow the light that came with him are the successful ones.”

Jeremiah 31 – A New Covenant

Even more explicitly, the Prophet Jeremiah announced that God would establish a new covenant distinct from the Sinai covenant. Jeremiah 31:31-32 declares: “Behold, the days are coming, says the LORD, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah – not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers in the day that I took them by the hand to lead them out of the land of Egypt, My covenant which they broke.” Notice the explicit contrast: the new covenant will NOT be “according to” the Sinai covenant. It will be fundamentally different. This prophecy from within the Hebrew Bible itself announces the supersession of the Mosaic covenant.

Some interpreters claim this prophecy was fulfilled in the Christian New Testament. Others argue it awaits future fulfillment. But the principle established is clear: God Himself announced through His prophet that the Sinai covenant would be replaced by a new and different covenant. To claim that the Torah covenant is eternal and can never be superseded is to reject Jeremiah’s prophecy – and thus to reject part of the Torah itself (since the prophetic writings are considered part of the broader Torah tradition). The Quran presents itself as the fulfillment of this promised new covenant – a covenant written on hearts, accessible to all humanity, and preserved from the corruptions that befell previous scriptures.

Part 7: God’s Covenants Beyond Israel

Esau, Moab, and Ammon – Divine Land Grants

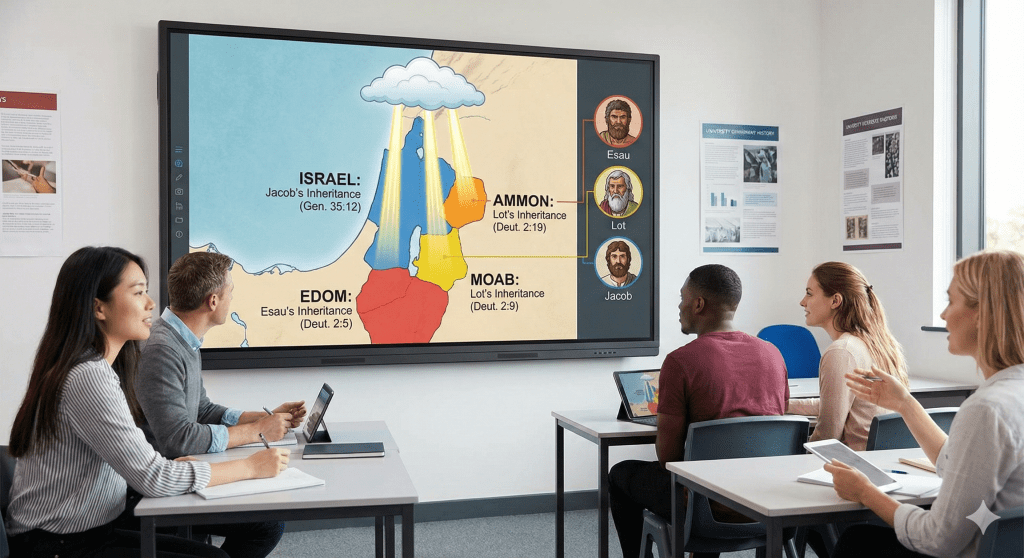

A striking feature of the Torah that undermines Israelite exclusivism is its clear acknowledgment that God made covenantal land grants to nations other than Israel. Deuteronomy 2:4-5 records God’s instruction to Israel: “You are about to pass through the territory of your brethren, the descendants of Esau… Do not meddle with them, for I will not give you any of their land, no, not so much as one footstep, because I have given Mount Seir to Esau as a possession.” God gave the land of Edom to Esau’s descendants just as He gave Canaan to Israel. This was a divine land grant to a non-Israelite people.

The same pattern continues with other nations. Deuteronomy 2:9 states regarding Moab: “Do not harass Moab, nor contend with them in battle, for I will not give you any of their land as a possession, because I have given Ar to the descendants of Lot as a possession.” And verse 19 regarding Ammon: “When you come near the people of Ammon, do not harass them or meddle with them, for I will not give you any of the land of the people of Ammon as a possession, because I have given it to the descendants of Lot as a possession.” The Torah explicitly acknowledges that God made covenantal land grants to the descendants of Lot through Moab and Ammon, parallel to His grant to Israel. God’s covenantal activity was never limited to Israel alone.

Melchizedek and Jethro – Non-Israelite Worshippers of the True God

The Torah also presents examples of non-Israelites who worshipped the true God outside of any Israelite covenant. Melchizedek, described as “priest of God Most High” (Genesis 14:18), blessed Abraham and received tithes from him – before the establishment of any Israelite priesthood or covenant. The text presents Melchizedek as a legitimate priest of the true God who existed completely outside the Israelite religious system. His priesthood was so significant that the Psalmist later declared the Messiah would be “a priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek” (Psalm 110:4) – a non-Levitical, non-Israelite priestly order.

Similarly, Jethro, Moses’ father-in-law, is described as “the priest of Midian” (Exodus 3:1). After the Exodus, Jethro declared, “Now I know that the LORD is greater than all the gods” (Exodus 18:11) and offered sacrifices to God. Moses accepted Jethro’s authority and implemented his administrative advice for governing Israel. A non-Israelite priest of the true God instructed Moses on governance, and Moses submitted to his wisdom. These examples demonstrate that God’s relationship with humanity was never confined to Israel. The Israelite covenant was one expression of divine providence, not its totality. The Quran’s claim to universal authority thus aligns with the Torah’s own acknowledgment of God’s universal activity.

Part 8: Torah Laws Given Specifically to Israel

“Speak to the Children of Israel”

Throughout the Torah, commandments are introduced with explicit reference to their intended audience: “Speak to the children of Israel” (Leviticus 1:2, 4:2, 7:23, 7:29, 11:2, 12:2, 15:2, 18:2, 19:2, 23:2, 23:10, 23:24, 23:34, 24:15, 25:2, 27:2; Numbers 5:6, 5:12, 6:2, 15:2, 15:18, 15:38, 17:2, 19:2, 33:51, 35:10; Deuteronomy 32:49). This formulaic introduction appears dozens of times, explicitly identifying Israel as the addressee of these laws. The Sabbath is described as “a sign between Me and the children of Israel” (Exodus 31:17), not a sign between God and all humanity. The Passover commemorates when God brought “you” (Israel) out of Egypt (Exodus 12:17) – an event in which other nations did not participate.

This specificity matters because it demonstrates that the Mosaic covenant was made with a particular people for particular purposes within God’s broader plan for humanity. The laws were adapted to Israel’s circumstances, history, and needs. They were not presented as universal legislation for all peoples in all times. When the Quran presents itself as a message “to all the worlds” (81:27), it claims a universality that the Torah itself never claimed. The Torah’s laws were for Israel; the Quran’s guidance is for humanity.

[5:48] “Then we revealed to you this scripture, truthfully, confirming previous scriptures, and superseding them. You shall rule among them in accordance with God’s revelations, and do not follow their wishes if they differ from the truth that came to you. For each of you, we have decreed laws and different rites. Had God willed, He could have made you one congregation. But He thus puts you to the test through the revelations He has given each of you. You shall compete in righteousness. To God is your final destiny – all of you – then He will inform you of everything you had disputed.”

The Dietary Laws as Punishment

The Quran provides a remarkable explanation for the extensive dietary restrictions found in the Torah. While the Quran itself prohibits only four categories of food – carrion, blood, pig meat, and food dedicated to other than God – the Torah contains far more extensive prohibitions. The Quran explains this discrepancy: these additional restrictions were imposed on Israel as punishment for their transgressions, not as universal divine law.

[6:146] “For those who are Jewish we prohibited animals with undivided hoofs; and of the cattle and sheep we prohibited the fat, except that which is carried on their backs, or in the viscera, or mixed with bones. That was a retribution for their transgressions, and we are truthful.”

[4:160] “Due to their transgressions, we prohibited for the Jews good foods that used to be lawful for them; also for consistently repelling from the path of God.”

This explanation accounts for why the Torah’s dietary laws are so much more restrictive than those given to other peoples. They were not God’s original intent for all humanity but a specific response to Israel’s behavior. The Quran restores the simpler, original dietary code that applies to all believers. Those who wish to maintain the additional restrictions as part of their cultural and religious identity are free to do so, but these restrictions do not carry universal divine authority.

Part 9: The Quran’s Position – Confirming and Superseding

Muhaymin – The Criterion Over Previous Scriptures

The Quran describes itself as “muhaymin” (مُهَيْمِن) over previous scriptures – a term meaning guardian, protector, witness, and criterion. This means the Quran serves as the standard by which previous scriptures are evaluated. Where they agree with the Quran, their teachings are confirmed. Where they contain corruptions or contradictions, the Quran corrects them. This is not a claim to replace the original Torah but to restore what has been lost and correct what has been altered. The Quran confirms the divine origin of the original Torah while acknowledging that the text we have today contains human additions and alterations.

[5:48] “Then we revealed to you this scripture, truthfully, confirming previous scriptures, and superseding them.”

The Quran’s superseding authority does not mean Jews must abandon their identity or religious practices. Rather, it means they must acknowledge the Quran as divine revelation and evaluate their traditions accordingly. The Quran explicitly calls the people of scripture to uphold their own books – but also to accept what has been revealed subsequently.

[5:68] “Say, ‘O people of the scripture, you have no basis until you uphold the Torah, and the Gospel, and what is sent down to you herein from your Lord.’ For sure, these revelations from your Lord will cause many of them to plunge deeper into transgression and disbelief. Therefore, do not feel sorry for the disbelieving people.”

The Torah Contains Guidance and Light

The Quran does not dismiss the Torah entirely but affirms its divine origin and the guidance it contains. Jewish prophets ruled by the Torah, and rabbis and priests bore witness to God’s revelation within it. The problem is not with the original Torah but with what happened to it over time and with those who failed to uphold it properly.

[5:44] “We have sent down the Torah, containing guidance and light. Ruling in accordance with it were the Jewish prophets, as well as the rabbis and the priests, as dictated to them in God’s scripture, and as witnessed by them. Therefore, do not reverence human beings; you shall reverence Me instead. And do not trade away My revelations for a cheap price. Those who do not rule in accordance with God’s revelations, are the disbelievers.”

This balanced approach – affirming divine origin while acknowledging human corruption – provides a coherent explanation for the textual evidence we have examined. The contradictions, the textual variations, and the theological difficulties in the Torah as we have it result not from God’s revelation being defective but from human interference with that revelation. The Quran comes to restore the pure monotheism that all prophets taught, correcting the distortions that accumulated over centuries.

Part 10: Jews Who Believe Will Receive Their Reward

The Quran’s Inclusive Message

One of the most remarkable features of the Quran is its explicit inclusion of righteous Jews among those who will receive divine reward. This is not a grudging acknowledgment but a clear, repeated affirmation.

[2:62] “Surely, those who believe, those who are Jewish, the Christians, and the converts; anyone who (1) believes in God, and (2) believes in the Last Day, and (3) leads a righteous life, will receive their recompense from their Lord. They have nothing to fear, nor will they grieve.”

This verse establishes clear criteria for salvation that transcend religious labels: belief in God, belief in the Last Day, and righteous conduct. Jews who meet these criteria are explicitly promised divine reward. The Quran does not require Jews to abandon their identity, their heritage, or their connection to the prophets of Israel. What it requires is acknowledgment of the truth – including the truth that the Quran is divine revelation and that God’s messengers must be heeded when they come with clear evidence.

The Pattern of Rejection

At the same time, the Quran notes a historical pattern among the Children of Israel of rejecting messengers who brought them unwelcome messages. This is not an anti-Jewish polemic but an observation rooted in the Hebrew Bible itself, which repeatedly records Israel’s rejection of prophets.

[5:70] “We have taken a covenant from the Children of Israel, and we sent to them messengers. Whenever a messenger went to them with anything they disliked, some of them they rejected, and some they killed.”

[2:87] “We gave Moses the scripture, and subsequent to him we sent other messengers, and we gave Jesus, son of Mary, profound miracles and supported him with the Holy Spirit. Is it not a fact that every time a messenger went to you with anything you disliked, your ego caused you to be arrogant? Some of them you rejected, and some of them you killed.”

This pattern is documented in the Hebrew Bible itself. Elijah complained that Israel killed the prophets (1 Kings 19:10). Jeremiah was thrown into a pit (Jeremiah 38). Isaiah, according to tradition, was sawed in half. The Quran simply observes this pattern and warns against its continuation. Those who rejected prophets in the past suffered the consequences; those who reject the Quran continue this pattern to their own detriment.

Part 11: Code 19 – The Mathematical Proof

Physical Evidence of Divine Authorship

The most decisive evidence for the Quran’s divine authorship – and thus its authority over previous scriptures – is the mathematical miracle based on the number 19. This is not a mystical claim or a matter of faith interpretation but a verifiable mathematical structure that pervades the entire Quran. The opening statement “In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful” consists of 19 Arabic letters. The word “God” (Allah) appears in the Quran 2,698 times (19 x 142). The word “Merciful” (Raheem) appears 114 times (19 x 6). The first chapter revealed (Chapter 96) is the 19th from the end. The first revelation consisted of 19 words comprising 76 letters (19 x 4).

[74:30] “Over it is nineteen.”

[74:31] “We appointed angels to be guardians of Hell, and we assigned their number (19) (1) to disturb the disbelievers, (2) to convince the Christians and Jews (that this is a divine scripture), (3) to strengthen the faith of the faithful, (4) to remove all traces of doubt from the hearts of Christians, Jews, as well as the believers, and (5) to expose those who harbor doubt in their hearts, and the disbelievers; they will say, ‘What did God mean by this allegory?’ God thus sends astray whomever He wills, and guides whomever He wills. None knows the soldiers of your Lord except He. This is a reminder for the people.”

Note that verse 74:31 explicitly states that the function of this mathematical code is “to convince the Christians and Jews” that the Quran is divine scripture. This is precisely the evidence that sincere seekers from these traditions need – physical, verifiable proof that transcends faith claims and enters the realm of testable evidence.

The Challenge to Produce the Like

The mathematical structure of the Quran cannot be replicated by human effort. Every aspect of the Quran – from the number of chapters (114 = 19 x 6) to the number of verses to the specific word counts – participates in an interlocking mathematical design that was impossible to engineer in the 7th century when writing materials were scarce and manuscripts were copied by hand. The messenger Rashad Khalifa, who discovered and documented this miracle through computer analysis, explained its significance: “This is the first physical proof ever that God exists and that the Quran is God’s message to the world” (at 0:23).

[74:35] “This is one of the great miracles.”

[34:45] “Those before them disbelieved, and even though they did not see one-tenth of (the miracle) we have given to this generation, when they disbelieved My messengers, how severe was My retribution!”

The Torah makes no comparable claim to mathematical structure. It cannot offer physical evidence of divine authorship because its text has been corrupted. But the Quran, precisely because it has been divinely preserved, contains this miraculous mathematical code as proof of its authenticity. Those who reject this evidence reject not merely a competing religious claim but verifiable proof.

Part 12: Deuteronomy 18:19 – The Command to Listen

The Torah’s Own Requirement

The most significant point for those who uphold the Torah’s authority is this: the Torah itself commands acceptance of future prophets when they come with God’s message. Deuteronomy 18:19 declares: “And it shall be that whoever will not hear My words, which he speaks in My name, I will require it of him.” This is not optional. Those who claim to follow the Torah are commanded by the Torah itself to accept prophets who speak in God’s name. To reject a proven prophet is to violate the Torah one claims to uphold.

The question then becomes: how do we know a prophet is genuine? The Torah provides criteria – the prophet must not teach worship of other gods (Deuteronomy 13:1-5), and his predictions must come true (Deuteronomy 18:22). Muhammad meets both criteria: he taught strict monotheism more consistently than any prophet since Abraham, and his prophecies have been fulfilled. But more importantly, the Quran provides something no previous scripture offered – physical, mathematical proof of divine authorship. This proof satisfies the Torah’s own requirements and then exceeds them.

[3:81] “God took a covenant from the prophets, saying, ‘I will give you the scripture and wisdom. Afterwards, a messenger will come to confirm all existing scriptures. You shall believe in him and support him.’ He said, ‘Do you agree with this, and pledge to fulfill this covenant?’ They said, ‘We agree.’ He said, ‘You have thus borne witness, and I bear witness along with you.’”

The Consequence of Rejection

Those who reject a proven messenger do not escape into neutrality – they incur divine judgment. The Torah itself declares this in Deuteronomy 18:19: “I will require it of him.” The Quran echoes this warning throughout, describing the fate of those who rejected prophets in previous generations. This is not a threat but a statement of spiritual law. To reject divine guidance when it comes with clear evidence is to choose Satan’s kingdom over God’s kingdom, with all the consequences that choice entails.

As the messenger Rashad Khalifa explained, the distinction is clear: “God’s point of view is that God alone is Lord of the universes, He has no partners, no other gods besides Him… And when you agree with this point of view, you belong in God’s kingdom” (at 27:16). The Quran brings humanity back to this fundamental truth – pure monotheism, worship of God alone, without the accretions and corruptions that accumulated in previous traditions.

Part 13: The Path Forward for People of Scripture

What the Quran Asks

The Quran does not ask Jews to cease being Jewish in any cultural or communal sense. It asks them to acknowledge the truth – that the Quran is from God, that Muhammad was a genuine prophet, and that God’s revelation did not end with the Torah. This acknowledgment does not require abandoning Jewish identity any more than accepting the prophets after Moses required abandoning the earlier tradition. Jeremiah was Jewish. Isaiah was Jewish. They brought new revelation that built upon and sometimes corrected what came before. The same pattern continues with the Quran.

[5:15] “O people of the scripture, our messenger has come to you to proclaim for you many things you have concealed in the scripture, and to pardon many other transgressions you have committed. A beacon has come to you from God, and a profound scripture.”

The Quran is described as a “beacon” and a “profound scripture” – light for those who seek it. The people of scripture are invited to benefit from this light while maintaining their connection to their prophetic heritage. What they cannot do is reject proven divine revelation while claiming to follow God. That would be a contradiction the Torah itself condemns.

A Call to Sincere Inquiry

The invitation is to investigate with sincerity. Examine the evidence for textual corruption in the Torah. Consider the internal contradictions documented above. Study the Quran’s mathematical miracle. If the evidence supports the Quran’s claims – and it does – then intellectual honesty requires acknowledgment. The choice is not between Judaism and Islam but between following God wherever His guidance leads and stubbornly refusing evidence out of cultural attachment.

[2:121] “Those who received the scripture, and know it as it should be known, will believe in this. As for those who disbelieve, they are the losers.”

The sincere among the people of scripture have always recognized truth when it came. Some of the earliest Muslims were Jews and Christians who recognized Muhammad’s prophetic authenticity. Today, the evidence is even stronger with the mathematical miracle discovered and documented. The question for each person is whether they will follow evidence or tradition, whether they will submit to God’s guidance or cling to human interpretations of that guidance.

Conclusion: The Evidence Speaks

We have examined the claim that the Torah represents an eternal, unchangeable covenant that supersedes all subsequent revelation. The evidence does not support this claim. The Hebrew word olam does not denote absolute eternity, and many “eternal” laws are no longer practiced even by observant Jews. The Torah contains genuine internal contradictions – regarding whether God repents, whether humans can see God, and whether God creates evil. The historical record demonstrates extensive textual corruption through the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Samaritan Pentateuch, and the Septuagint. The Torah itself prophesies the coming of future prophets whose words must be heeded and explicitly announces a new covenant that will not be like the Sinai covenant.

The Quran comes not to destroy the Torah but to fulfill and correct it – confirming what remains true while correcting what has been corrupted. It offers what no previous scripture can: mathematical proof of divine authorship through the miracle of 19. This proof satisfies the Torah’s own criteria for validating prophets and exceeds them. Those who sincerely follow the Torah are commanded by the Torah itself to accept proven prophets. The Quran provides the proof; the choice to accept or reject is each person’s to make.

The path forward is not one of religious conflict but of sincere investigation. Jews who believe in God, believe in the Last Day, and lead righteous lives are explicitly promised divine reward. They are invited to examine the evidence, to study the Quran’s claims, and to make an informed decision. The same God who spoke through Moses speaks through the Quran. The question is whether we will listen.

[5:19] “O people of the scripture, our messenger has come to you, to explain things to you, after a period of time without messengers, lest you say, ‘We did not receive any preacher or warner.’ A preacher and warner has now come to you. God is Omnipotent.”

Leave a comment